Virtually tour the Abbot Mill Exhibit in the

Westford Museum with Penny Lacroix (2007)

Helene (Mickey Crocker reflects on her years working in the Mills (2021)

Working the Mill in the 20″ Century

A view of the Abbot Worsted Company and the community it created

By Penny Lacroix (2007)

In the 1790s, in the newly formed United States, entire towns sprung up along rivers specifically for the purpose of processing cotton into yarn. Entire families worked alongside each other in those first mills. Conditions were poor, hours were long, and the companies took advantage of employees’ economic situation.

When the Industrial Revolution truly took hold in Lowell, MA, and surrounding areas in the 1820s, girls were recruited from farm communities in northern New England to live and work in the industrial cities. Initially, the situation seemed to benefit all, but as companies demanded more and more of their workers, the “mill girl era” waned. The Yankee girls were gradually replaced by immigrants from Ireland, Canada, England, Scotland, Russia, and other European countries, who would work for lower wages.

Massachusetts was a leader in child labor reform, being the first state to enact restrictions on child labor in the U.S. The 1837 Massachusetts law prohibited manufacturing establishments from employing children under the age of 15 who had not attended school for at least three months in the previous year. Laws also prohibited children under 14 from working in the mills at all. However, children, especially those of poor immigrants, were still found in the mills.

As the 20″ century neared, workers demanded better conditions and more pay. Early strikes were unsuccessful, but eventually, a series of labor reforms were enacted by the government and by the businesses themselves, gradually improving working conditions, hours and pay. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs in the 1930s reformed business even further. As a result, the textile mills of the 20″ century were a far cry from what we all learned in our history books about the early textile mills of the Industrial Revolution.

In 1883, 200 people were on the payroll at the Abbot Worsted Company located in the Forge Village and Graniteville sections of Westford, Massachusetts. They worked from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. Monday through Friday and until 4 p.m. on Saturday, a total of 64 hours a week. The annual consumption of wool was 2,250,000 pounds.

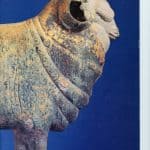

By 1916, the year the Adamson Act established the 8-hour workday with additional pay for overtime, the Abbot Worsted Company was the largest manufacturer of carpet worsted yarns not only in this country, but also in the world. The total production was

4,616,826 pounds of worsted spun carpet yarns and 278,504 pounds of camel hair yarn. These yarns required the wool from 2,155, 380 sheep and camel hair from 1 7,14 4 camels.

Through the war years, the depression and labor reform, the Abbot Worsted Company continued to thrive, employing 800 people in Forge Village alone in its peak years. During World War II, they turned to making wool for uniforms and bussed workers from nearby Lowell to supplement the local workforce. But what made the Abbot Worsted Company special? Why did they survive so much longer than other textile businesses in the north?

In preparing for an exhibit at the Westford Museum, I had the opportunity to interview several people still living in Westford who worked for the Abbot Worsted Company before it closed in 1957. I was assisted in the interview process by students and advisors from the Westford Academy Museum Club. Most of the people interviewed still live in Forge Village.

From these interviews it was obvious that the Abbot Worsted Company made a conscientious effort to keep its employees happy. The company provided low-cost housing, which they kept in good repair. There were no labor unions at Abbot, but according to the National Register of Historic Places nomination for Forge Village, wages were the same as those of union employees. Like many companies in the textile industry, they recruited textile workers from England and Scotland not only for their industrial skills but to play soccer for semi-professional, company-sponsored teams.

Abbot built and maintained a social hall where employees and their families could gather for movies, dances, and other social events. Before medical insurances were available, the company provided a hospital and medical services not only to its own employees, but to their families and members of the local community as well.

Most of the Forge Village children attended the local Cameron School and then went on to Westford Academy, the public high school in town. For those who were not planning to go to college or into military service, the mill was a common choice.

Arnold Wilder, now 98 years old, was the personnel director for Abbot at Forge Village. Arnold was an avid horseback rider. (He was active in the Westford Minutemen, so locals remember Arnold riding his horse in local events during the American bicentennial era.) One of his favorite stories is about a bad snowstorm while he was working at the mill. None of the roads were passable, so Arnold took his horse to deliver the payroll! This dedication was promoted by the Abbot family throughout their business.

Tom Holmes worked in the mill for a total of about 8 years, before and after World War IL His parents both worked in the mill, his father for over 50 years. “My mother and father rented a house on Prescott St. in Forge Village. I think they paid $19 per month rent. The Abbot Company took care of everything. If you had a broken window, you called the office, and they sent a crew out to fix the window. Or if you wanted new wallpaper, you called the office, and they sent a crew up to wallpaper for you. They wallpapered the house for you. They took care of everything. They manned the whole village. Graniteville, too.” In the late 1940s, when the Abbot Worsted Company began to sell off property, the resident employees were given first option to purchase the houses at low market prices.

And what about that timeless issue of childcare? Many of the mothers quit working when they had their children, but especially during the war years, numerous women filled positions in the workforce. Tom Holmes’ family managed while both his parents worked. “School started 8:45 in those days, and I was at Cameron school. My father started work at 6 in the morning, and he would work straight through until 2 in the afternoon. My mother would start work at 2:30 in the afternoon until 10 at night, 11 at night. So, when she’d go to work, he’d come home. There was always someone there to take care of us.”

Mickey Crocker, a well-known, lively lady in town, started working part time in the mills before she got out of high school and continued until she had her first child. Her grandfather was recruited by Abbot and moved from England to Forge Village when her father was 8-years old. She remembers from her own youth, “You didn’t have to leave Forge Village. It was self-contained. You had a fish shop; you had a bakery; you had a First National [store]; you had a Clover Farm [store]; you had an economy store, a drug store, the depot, [a] yarn[shop].” Handley’s yarn shop was located across the intersection from the mill in Forge Village. Of course, skeins of yarn from Abbot were sold there. (This building, incidentally, is where in the mid-1800s Huldah Robbins Prescott had raised silkworms and reeled the silk into skeins to sell.)

One of Mickey’s many jobs with Abbot was that of “checker”. As a checker, she would weigh and record the full bobbins, or “doffs”, for each operator, weather she was in the spinning room, the twisting room or the winding room. The operators’ pay and bonuses were based on their time worked and their productivity. Each lot of wool was carefully tracked so that every product could be traced specifically to the original raw materials, the various workers who had processed them, and the cost of each.

Mary Cote also grew up in Forge Village in a family with many ties to the mill. She remembers her parents working in the mills. Her aunt, Mae Lord, was the town nurse and the nurse at the Abbot hospital. Mary herself worked in the winding room before she finished high school and later became a checker in the sorting room. This was a sought after job, as it wasn’t as physically demanding as many of the other positions.

Mary recalls the social opportunities created by Abbot. “At the hall they had movies. They had movies three times a week. They had a men’s club and a women’s club, and in the men’s club they had bowling. And they had a [juke box.] They had a semi-pro soccer team. Mr. Abbot paid the men to play on that team and some of the men, like my uncle Billy Kelley, was a boss in the mill.” The Abbot band practiced in the hall as well. With company-provided uniforms, instruments and music, the band played for concerts, parades and other functions throughout the town. When asked about her best memory of working in at the Abbot Mill, Mary Cote replied, “I met my husband there.”

Dotty Caless, whose parents were farmers in another part of town, remembers that the Abbot Worsted Company gave small gifts to all the first and second graders in the entire town at Christmas time. “The gifts from the mill were so unexpected, that when we were handed the wrapped gifts, we were so overwhelmed, as a gift was placed into our hands, that we could hardly believe that these gifts were really ‘ours’ alone!”

By the 1950s, most of the textile industry had already moved south where wages and operating expenses were lower. Despite the Abbots’ care and attention to their employees’ quality of life and their community, the Abbot Worsted Company eventually followed suit and sold off its property in Forge Village and Graniteville, closing its doors in 1957. The mill buildings in Forge Village were purchased by Murray Printing and then by the Courier Corporation. Today the Abbot mill buildings still dominate Forge Village, and there are plans underway to convert the old buildings into high-end apartments, preserving their historical integrity.

Resources:

Johnson, Sandford, Nominations for the National Register of Historic Places,

Westford Historic Commission, March 2003.

Welcome to Abbot Employee Handbook,1946

The Abbot Worsted Company; The Business, the People and the Community

In 2006, prior to the conversion of the Abbot Mill buildings into residential units, Alan Chaffee received permission from the owners to complete a thorough photographic survey of the existing buildings. Alan generously made these photos available to the Westford Historical Society and the public. Enjoy your virtual tour, click here! Abbot Mills Photo Tour