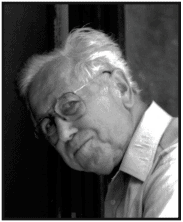

Alex Belida was truly Westford’s Russian historian. He gave generously of his time to schoolchildren and to the Westford Historical Society, lecturing on every phase of life in Westford’s Russian community: religion, education, weddings, food, work, funerals and graveyards, and home life. His parents were first-generation Russians who met in Westford, fell in love, married, and settled in Graniteville.

Academic education was of utmost importance to the first, second, and third generations of Alex’s family. How proud they must have been when Alex’s daughter, Nancy, was salutatorian of the 1967 Westford Academy graduating class.

From 1970-1973, Alex served on the J.V. Fletcher Library Board of Trustees and gave endless time as a volunteer to the library.

Alex was a pillar in the Westford Historical Society in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, serving as president for many of those years. When the Westford Museum was founded in 1983, he gave a decade or so of physical labor by building shelves and cases to enhance the exhibit and storage facilities. Alex lived with his wife, Bernice, at 65 Dunstable Road.

Westford’s Russian Community

The Russian colony that was here came in the early 1900s, anywhere from 1901-1912 or 1913. They came here because the mills happened to be in Westford and, not being educated, and unskilled, they were taken into the mills or quarries for work. Their intention was to come here, to come to Westford or to the United States, earn a goodly size of money, and then go back again. Very few actually intended to stay. However, World War I erupted and they couldn’t get back. Many of them made this country their home. They stayed on, got married, and raised families.

They used to get together on Sundays or Saturday nights, and just talk over old times. I remember them saying that when they were back home, before they came to this country, Jewish agents – recruiters – would come in. In Russia at the time, they had to live in a hut, sort of, with a thatched roof, one big room, and a big, big stove, like a bakery stove. They were living at the lowest ebb. I can see where most of them would want to come here. They would have animals in there, in the back, so things were hard pickings.

In the early 1900s there was a large demand for labor, unskilled labor, in the United States. So they would go down recruiting. Nevertheless, it was illegal to leave Russia just because you wanted to come to the United States. So they would have to go through Germany or somewhere else to get smuggled out. The agent, to entice them to come, would say that the Czarabakees workings were so great, and in great demand. There were such good pickings there [United States], that if you did go, you didn’t even have to get a job. All you had to do was walk the streets of New York and in about an hour’s time you could pick up enough coins on the streets to earn a living that way. That’s how good it was living over there. So, of course, people would get amazed and would apply, and they would pay a fee somewhere. I don’t know how they got the money, but sometimes they would borrow it from all the neighbors – enough to send one person out.

When that person got to the United States they would send money back, after they earned it. A lot of them sneaked down through Germany. It was like an underground railroad, and, of course, that all had to be paid for by certain agents. From there they would board a cattle boat and go to England. I think – I’m not sure – I think it was Liverpool. I’ve heard them talk of Liverpool. Then, from there they would take a slow boat, maybe a freighter, to the United States. It could be a passenger ship, but it would be of the lowest class. I think my mother came on the Bremen, the German line of Bremen. I’ve forgotten my father’s boat. When the people came here, they would have to earn enough money to repay the passage to whoever had lent them the money. Things were pretty rough, but they made it.

When they came here, you were supposed to go through the immigration. They were told – I suppose there was a tag on you -where to go. [Some] names were changed because the immigration officers couldn’t pronounce them. There was a fellow I knew by the name of Kuccuokski. When he was being processed, the chap that was doing the processing at the immigration station couldn’t pronounce it or write it. So he said, “Your name from now on will be Carson,” and he died with the Carson name 60 years later. So, for a lot of them you cannot tell the nationality of the person by name, because they were changed there. The person didn’t even know it was being changed. Eventually, those that did come would come to, say Westford, to live. Probably the next day, they would go down to the mill and apply. They would sign them up real quick.

There are several [Russian families]. For instance, we have the Minkos; anything that ends in O is generally Slavic. My name is the only one that I don’t know what it means – Belida, but in Russian it’s called Beida. They have a liquid L that we don’t have in the English language. It’s a French L. Secovich, Harasko, Delanski. Actually their name is Perrimit, but they Americanized it because it’s hard to say. There’s Kazeniac. [Some] simplified it to Kosnac. There’s Sudak. Sudak used to be a storekeeper up in West Graniteville [former Graniteville Schoolhouse No. 10].

The Grodno Cooperative Store

Of course, Westford being a small rural town, they were limited in a lot of things such as stores, transportation, and everything else. So the Russians, back in the mid-’20s, organized a store or food cooperative. Since many of these people—there were about 40 or 50 families—came from in and around Grodno, which is a city and county in Russia on the border of Poland, they called it the Grodno Cooperative. They organized their first store in the Forge Village section of Westford [Spinner’s old store at 2 West Prescott Street]. That kept going for about 10 or 15 years.

Later, it was on Pond Street [#9] at the bottom of the hill. When you come in from Pleasant Street, go down to where the steep hill starts and it’s on the left; it fronted on the Mattawanakee Lake or Forge Pond. That flourished, and from that store they had a butcher cart – a wagon – full of groceries, meats, and so forth, that went out into the farm districts and to homes that were too far away for people to walk to the store. I remember my father worked for a few years doing that for the Grodno store. Finally, Graniteville had such a demand on the grocery wagon that they decided to build another store in Graniteville. It was, at the time, at the corner of River, Beacon, North, and North Main Streets – what is known as Greig’s Corner or Brule Square. That store flourished until just a few years ago, when the supermarkets started to bite into the business. So I believe it was two years ago -this is 1977. Last year, 1976, it finally closed its doors. The cooperative was disbanded and another store is now there. The name of the store that was in Graniteville was Grodno Cooperative #2. For the longest time they did a good business.

The people that owned it – and, of course, we [members] were owners of the store – shared dividends every year. After the business had all been paid – all the expenses and taxes – the rest was divided among the members. In that store you didn’t have to buy for cash, but you could buy it on the book and pay weekly. The person got dividends according to the total that he bought from the store. If you bought very little, you got very few dividends. On the other hand, they also had cash discounts for customers – not members, but customers. They could bring in their cash register slips and get so much for that, too. At the time, for six or seven years, I remember being on the board that was governing that store. First we closed the Forge Village store, and then about 10 years later we finally had to close the Graniteville store. It’s now in some other company’s hands.

Russian Brotherhood Cemetery

The Russian cemetery setup was similar. Everything is chartered under so many members. Some could be members of the cemetery and not the store; others belonged vice versa. The store was organized and licensed in the state as a cooperative, not just a company. It was a cooperative. I think they copied that from many of the towns, like Lawrence. And Maynard had a big Finnish cooperative over there. So apparently the foreign people were intrigued with cooperatives. It was sort of a brotherly setup.

The Russian cemetery was organized in 1918 during the influenza [epidemic] period. When the Russians first came over, they were of the Eastern Orthodox religion, which closely resembled or fitted in with the Catholics at the time. However, during one of those years, a priest was assigned to the Graniteville district [St. Catherine of Alexandria Roman Catholic Church] who said that if you’re not a pure Catholic, you could no longer be buried in the cemetery. They had been buried there for the previous eight or ten years, ever since they came to this country. I don’t mean that there were a whole lot of them that died from influenza, but some infants were born and were buried there. But they had to then find a way to bury their dead when the time came. They did not know enough to go to the town and apply for graves. They figured the town probably belonged to some other religion.

So, on the spur of the moment, my father and two or three others organized a committee. They went up to Westford, to the authorities or the powers that be, so as to organize the Russian Brotherhood Cemetery. They came down and showed where they wanted the cemetery to be [on Patten Road]. An attorney by the name of Mr. Fisher came down. I remember, when I was a small boy, they say he paced it off. He said, “This is where your bounds will be.” He did the paperwork for them. It was 1 acre that they bought. Then in their spare time they went up and cleared the bramble, all the scrub oak, and big trees, and they commenced burying the people there. Today, anyone can be buried there, providing they are a member. You have to be one of the descendants of the people that are in there. Now, they’re not all Russians. Some of the daughters and sons intermarried with other nationalities, so they can also be buried there. However, we discourage selling lots to just anybody because we don’t have a permanent caretaker. We have a fellow that comes in and mows once in a while for us, which we pay for. If we sell [lots] to anyone, it will be overrun. We’d have a lot of work, and it would no longer be a good buy to own a grave lot there.

A member, when they become of age, pays $2 a year. It used to be 50 cents a year. Then it went up to a dollar and so forth. Now it’s $2. I suppose it could be called a cooperative. When you join, for instance, if the person at the time had a family, you were allowed as many graves as you wanted, and it was still only $2 per year for the dues. As the people got married, they had two years to join, and it was $2 a year. We have a goodly number of members now. I happen to be on the governing board or the committee, and I’m the secretary. We meet twice a year to clean up the cemetery ourselves. There’s where the savings comes, as we do the work ourselves like our forebears did.

If you walk into the cemetery you will notice a lot of gravestones that are lettered in the Russian alphabet. The old Russians naturally went to school under the old Czarist system. The Czar, as you remember, was overthrown in 1917. Under the old Czarist system they had a type of alphabet that had excess lettering in it, certain lazy vowels that had to be put in grammatically. Anyone that is familiar with the Russian language would understand that. When the Bolsheviks or the new government took over the power in Russia, the first thing they did was lop off six or seven letters that were of no value, and therefore made the language much simpler. When you go to this cemetery, you will find that the ones who were buried – who were of the old Czarist education – used the old lettering. Then, as you progress into the ’20s, you will notice that the newer stones were in the newer type of language. Now we have changed all that. As the newer generation is growing up, we have done away with the Russian language. We put on the English language like everybody else, and you can read it.

When they started burying, I suppose they didn’t know to line up the stones and graves in the proper way. They just dug a hole. Anybody could go up and dig graves in those days. No formal digging like there is today with the machines. Whoever dug never thought to line them up, so the stones were quite a bit haphazard. Later we realigned them. A lot of them had no foundations and had to be redone.

I think the back land belonged to the Westford Water Company or to Rooks on the other side, one or the other. That was before I was on the board. I must find out. Mrs. [Marilyn] Bretton, who was on the Historic District study with me, wants some of that information. I keep forgetting to ask the old fellows. Out of the original bunch, I don’t think there are six left of the Russians. They’ve got one foot in the grave now, actually, poor things. But just as chipper, they come up with their rakes and their shovels, and they try to do what they can, you know. One man can just barely toddle, but he says, “I’ve been coming up here for so many years. I’m going to be here until they bury me here.”

They’re in their 80s now, some of them. The only reason the others died off was cancer, tuberculosis, or something like that. Most of them all died in their 70s.

The [burial customs] might have been a little fancier in the olden days than the Catholic customs. Of course, Protestants have a very simple ritual, which is the way, as a Protestant, I like it. But in those days, when the burial came, the priest would come up in his regalia and consecrate the grave. The priest resembled one of those Greek priests. Then he would deliver a lecture – the same thing as somebody would from the pulpit. Everybody stood around shifting weight from one leg to another, very uncomfortable, especially in the summer when it was very hot. After that they buried them. Then they went home. Of course, the mourners would cry, bawl, and carry on.

Some of the older ones still practice the wailing custom. Some of the newer ones try to copy it a little bit, but it doesn’t look good in America, so we’re cutting that all out. In fact, I know when I buried my mother here, three or four years ago, we had a private funeral and there was nothing. That’s the feeling of most of them now, and to do away with the expensive frills.

Church & Weddings

The Westford Russian community being too small, there wasn’t enough to support a church here, so they never built one. But they’ve always had one in Lawrence and in Maynard. Generally they would ask the Maynard priest. I was born and baptized into the Eastern Orthodox or the Russian Orthodox religion. I am recorded in Lawrence for some reason. I suppose maybe my folks happened to be there or had friends up there that were more influential than in Maynard.

One time [I went to the church service with you parents]. To me, it’s kind of a long, dragged-out affair. For instance, on Easter they congregate early in the evening, and some evenings it’s very cold on Easter. They get into a procession and walk around the church with the priest holding a candle, and all of his officers behind him. I don’t know what they are – deacons and so forth. They walk around and around and around, which is supposed to cast off evil spells. I don’t recall much of the rest of it, but in Russia, especially, this is done. Russia, of course, being of a colder climate than here, they really were bone-chilled by the time they got in. The churches were great big barns, well made. The congregation may be the poorest in the nation, but they had a big church.

When they walked in there was no such thing as a pew. When the Russians came to this country and saw seats in the churches, they thought this was some kind of fallacious thing, because you are supposed to stand up for God. So they’d stand there for hours and hours while the priest harangued the politics [gave a long, passionate, sermon].

They wore hats [to church]. The men took their hats off like we do in the United States. The women always wore babushkas. In fact, to this day, particularly the Russians, Polish, Lithuanians, some Finns and Greeks – you will see them wearing them. It’s from the old tradition.

[The services] were very long. My mother said when she was a little girl the kids didn’t like them because they were too long. They were slapped fast if they ever interfered. Everybody was supposed to stand quietly. They did have one thing nice about them; the choirs were very good. The Russians are naturals at choirs, just to get off the subject of religion for a minute. For instance, when they have weddings here (this is a gone-by era, I’m talking about the ’20s and maybe the very early ’30s), there would be a great big bash, and they’d spend all kinds of money.

There was nothing that was too good for the bride and groom. Generally the bride’s folks did the entertaining. This would start Friday night or early Saturday morning. Saturday forenoon, about nine or ten o’clock, they’d take off to be married. They would have to go to either Lawrence or Maynard, out of Westford. I remember I played in a little orchestra that played for the dancing. The dancing could be in the living room or the biggest room they had in the house. This is before dance halls were around. The room was stripped right down to the bare floor, because they really got rambunctious. They had a few chairs. When they left, we’d play them a certain type of bride’s march. They were all escorted out. They got in the cars, and there was much to-do. Finally they would take off, blowing horns all the way to Lawrence. I imagine a few times they were told to cut it out by the police, because they were really raucous. Anyway, they’d come back, and we’d play an entry march. It was all a big deal, a certain procedure that they went through.

When they had these wedding blasts, you see, they had all kinds of food, homemade kielbasa—those were good. There’s one thing about the weddings; they never were short of food or drink. The family provided it, but everyone came over and worked with you. Like for instance if you were to get married, all the women that your mother knew would come, and for days and days they would prepare stuff, like kielbasa—and they made kielbasa by the tons, you know. If you went home hungry and thirsty, it was your own fault. They’d make all those fancy pastries and things—not too many of them, but the ones that were there were fancy. They cooked different kinds of meat. They never had chicken. Then, chicken was nothing.

It’s a funny thing. They never brought any presents for the bride. It all had to be in greenbacks. They always made a big cake – two, three, or four tiers high. When the time came for the donating, everybody got up close and donated $5, $10, $15, or whatever they wanted. There was always big money. Even during the Depression people would save for that kind of a wedding. They’d get a piece of cake, or if they didn’t want cake, they’d get a shot of booze, even during Prohibition. For some reason, nobody bothered them. When all the cake was gone, there’d be a big basketful of money. That puts us Americans to shame, the way they did. Eventually, the bride would throw the bouquet. Finally, the groom would kiss the bride, they’d break up, and they’d go off somewhere for their honeymoon, I suppose. We didn’t know.

My brother, myself, and a few others were in the little orchestra that entertained, and, boy, entertain we did, because there was a heavy demand for music. When the people came they gave the musicians a tip, which was a quarter or something. There was generally a box there, or they put it into a violin or a guitar front. At the end we split up the profits, whatever they were. That’s the way the weddings were conducted. The mother went through a certain ritual of crying about her bridal daughter’s leaving.

Most of [the wedding dresses] were homemade, because in those days I don’t believe there were many local places that made wedding gowns. I have a picture somewhere of my parents’ wedding.

The Episcopal Church’s pageantry and the mass is the closest [to the Russians Orthodox service]. The Protestants conduct too plain a service, which I like myself. They like that pageantry. So they go to this day, and to them it’s very impressive. Some of them were Protestants, but for some reason they never went to the Unitarian Church. They seemed to think that was something that’s just not for them. I was the only one that attended that one. Some went to other churches, like Baptist, but most of them are Episcopalian to this day.

Christmas

Russians never celebrated Christmas much at all. They were just like the old Yankees that came here, the old Puritans. There was a Christmas when the kids got older and they observed Christmas in the schools. I believe they brought a different atmosphere to it. I never believed in Santa Claus right from the beginning, myself. But that’s me. In Russia they have a Santa Claus, only it’s not a Santa Claus; it’s Granddaddy Frost, Grandpa Frost – Dedushka Moroz, they call him. He wasn’t supposed to be a gift giver. He was supposed to be a cheer bringer. In the old country, they never had Santa Claus with presents. It was good cheer. They’d get together. You came to my house, and I gave you a drink or we dined or feasted. But there were very few presents. In fact, when the Russians first came here, they were amazed at people doing that.

My mother said at the time they first came here there were no Christmas cards [sent by Russians]. Later on, Christmas cards caught on, and once in a while someone would send a postal card. I remember for the longest time I had a postal card of Santa Claus. It was just a plain postal card, as we know it. Of course, today they send cards in envelopes, as if it were a big business. But in those days they didn’t. I imagine some of the American people will remember that, too. They’ve really commercialized Christmas today, in my estimation.

If a person, maybe a daughter gets to be 16, we’ll say, … I remember several birthday incidences where they’d sit the kid on a kitchen chair, and they’d raise her maybe the number of years that she was. She was supposed to scream. Then they all would flood her with dollar bills.

There was one thing that I used to like when I was a little boy – to sit in with the men when they were talking about their experiences in the wars. They’d make their stories so interesting that you’d want to sit there and listen and listen. If anybody was an ex-soldier, he would relate some of his experiences in the service. One fellow that I knew was in the Army. He was transported from regular Russia over to the east coast, which is across Siberia. He told of the experiences that he went through, how they stopped at different stations and these Tartars came out, and how they had baked chicken for 2 cents. He made a regular volume out of it and made it sound so interesting. You’d have to listen to it yourself to appreciate it.

Russian School

There was a Russian school in Forge Village. I had forgotten all about that. I think they had one at Florian Woitowicz’s house [Woitowicz home, 15 Story Street]. It was underneath in the basement. We learned to read there. I learned how to read before I went to one of those schools. Later, they had a school in Graniteville on Maple Street in a house that is no longer there. It burned down. I went there for a little bit. Finally, the students had no place to go. Up in West Graniteville there was a fellow that owned a little dance hall. He had built the place on speculation, but there weren’t too many dances held of any kind. This was during Prohibition and the Depression, so there weren’t too many things going on. So he rented that out for a Russian school. I found out many years later that the school benches and desks that were used came out of [Lyon] Schoolhouse No. 9. Whatever happened to those desks, I don’t know. Those desks and chairs would be treasures, of historic value. They probably dumped them, because at that time they were of no use. We had three classes in there on the same order as our little red schoolhouses in America. I was up in the highest one. Then they had the second class. Then they had the A, B, C crowd. There were maybe about 25 or 30 kids that attended. No customs were observed, no indoctrination of any kind. We learned to read and write, period! I know Russian writing and reading to this day, on account of it. I went to school and studied a little bit in the Air Force, but that just brushed over it.

[At home] we spoke Russian. In fact, when I was three years old I could read simple Russian because my folks always had read Russian. My father went to night school and gradually learned to read English. He went to Lawrence one time. Later on, they had night school in Forge Village at the Cameron School. He went there, too, for a long time. If you want to learn a language, and you start looking through simple books, eventually you’ll learn how to read. English, I suppose, is quite easy once you get the hang of talking. A few of the men, I would say [out] of the 40 or 50 families at the time – maybe five or six – knew how to read, and the rest couldn’t. Gradually, the men learned to read and to talk enough, and maybe the exams weren’t as rigorous in those days, but they finally got their citizenship papers – most of the men that I remember.

But for the women it was taboo, and they were afraid. None of them could read or write. It was actually against the law for women in Russia to know how to read, and they kept their station. My mother was the only one of the Russian women that could read Russian, and later she learned English.

A few years after I came home from the service in 1946 there was a citizenship class that opened in a little hall under the Grodno store in Graniteville. However, the teacher that was sent up there from Lowell, an area teacher, was French. They had all types of women in there learning, but the French got the best deal because the teacher could translate or explain in French anything that the French women couldn’t understand. But the Russians sat there and didn’t know what to say. So gradually they drifted out of the class.

My mother, who had already gotten her citizenship papers said, woefully, one time, “It’s a shame that the school is there and no one understands.” So I got to thinking one day – my mother was pretty handy with tools – and I said, “Ma, if you can build a blackboard, and if you want to invite them to this house, I’ll teach them how to read and write. Then maybe they will have gumption enough [be inspired] to go for their papers. I’d like to see them get their papers before they die.”

My mother’s house was at [19] North Street. Sure enough she made one, and in about a week she said it was all done and painted. She invited about a dozen women. They came, but they were very skeptical. “For us to learn! How can we? We’re too old!” I took them from one letter to another and taught them how to assemble sounds. First thing you knew they could read a few letters, a few words; finally after that six-month time, they could read brokenly. They would call me on the phone, or when they’d come up to my mother, they’d say, “Do you know what I read in the paper?” When they did that, it whetted their appetite for an education. People [Russian men and women] were hungry for enlightenment. This and that, it would be some little thing and it so enlightened them. It made me feel good.

Finally about eight or so of them got the courage to apply for citizenship. Two or three or four of them were too afraid and never did get it, but it was their option. I taught them how and actually helped fill some of the citizenship forms out. Then they were waiting just like a cat on a hot roof. Finally the day came, and they went down there. I think it took two or three times to go down – I don’t know what it was. It was in the North Middlesex County Court in Lowell where they give out the citizenship papers. On that day, the French teacher was there who taught the others. Naturally she grouped them all together. When the papers were all handed out to them, she had a special choir of girls and boys come up and sing a few patriotic songs. It ended up on a nice note. Those women treasured those papers something fierce. It wasn’t too many years later that they all passed on. I felt good that they at least died American citizens.

I was born in Westford on November 29, 1918. I was born in Forge Village. It was in a house opposite the Forge Village Post Office [located at 5 West Prescott Street] hich is now occupied, I believe, by the Bohenkos.[Later the Stifler home]. In those days you were born in the house. There was no such thing as going to the hospital. These were tough times; women were rugged..

[The Russians settled in both Graniteville and Forge Village.] The reason they settled here was because they had mills in Forge and Graniteville. Some worked in the quarries. My father worked at L.B. Palmer’s and Sons Quarry for the longest time. My father was not a mill man, but later on he went into the mills when the quarries closed down.

People that worked in quarries, or other seasonal jobs, would wait until the ice harvesting came around. In those days they had these big machines that cut ice, with horses dragging them along. They lost a pair of horses up there in Forge Village, as you probably know. They would cut the ice all up and float it in. We had two or three Russians that were really husky. There was Steve Kovalchek, for one, who was an A-number-one icer. As the ice blocks went up the escalators, they would fill the first floor. Every time they would put a layer of ice down, they would douse it with sawdust to keep it from melting. Then when that floor was filled, they would go up to the next one. Well, Steve was the one who would steer the ice to its destination. That meant that he had to be heavy and strong. If he weren’t, the 2- or 300-pound blocks of ice would pull him right off his mooring. Steve was always a good iceman.

Abbot Mills

A lot of Russians did work in the Abbot mills. That was the main attraction, and contrary to what they say – that things were good – things weren’t so good. I remember my mother saying that when they came over as youngsters they had to sleep two or three or four in a bed. So it was rough. They came on the invitation or the sponsorship of some older Russian that was here. Some of them came in the late 1800s. They would establish themselves and get a home. Gradually, as the town started to get flooded with prospective employees, there were no more homes. So all right, you got married and you’re one of the boarders, so now you need a home. You go down to the office and you apply for one. He’ll say, “We’ll give you a home when you need it, but first I want to have you guarantee that you will have six boarders.” So in a four-room house, you really didn’t have much room. Some slept in cellars, which is not a healthy thing. Contrary to the fact that they figured this was the land of milk and honey, it was really just as tough. In Europe there was no work. So they came over here, and this was a big deal for them. There were outhouses, and they burned wood for fuel.

[The houses were] company houses, and some of them were located on Canal Street, next to the canal in Forge Village. I’ll take Forge Village first. Canal Street had a block, plus a few singles. If you were really in with somebody, you could have a single, provided you had a few boarders with you. The blocks also had families, but they also had boarders with them. In those days you probably paid $1 or $2 a week for room and board and washing and everything. They had some on Bradford Street and Pond Street. If you go down through Forge Village today, you will see a lot of little company houses. Now they have decked them up and expanded them a little.

In Graniteville they were more spotty. There weren’t that many company houses in Graniteville. A lot of them were for Sargent’s machine shop. But they had Beacon Street, which was called a block, plus a couple of houses there. There were private houses that were rented out to people, too. The biggest company cluster was right around Forge Village. Later, Brookside [Nabnasset] started to mushroom, too, but the Russians never went there. Others went – I think maybe the Italians, Irish, and English – [and the Swedes].

[In the mills] most of the Russian women were skilled, and they learned to spin. The men started down in the card rooms and the washrooms – the heavy work, where the women wouldn’t or couldn’t work. I spent a little time in the mill, so I know the industry myself. I curse it. They all worked hard.

They never went to school at all. The school [Academy] was for our generation. The grownups that came over never went to any school other than maybe a little bit of night school. Mr. Secovich went – he’s a distant cousin or relation of mine – and maybe two or three others. When we were kids, I know my father went, and he could read. Some of the more enlightened men went to school on their own. Others just learned to speak English – at their workplace, and around the house using English. That’s all they did. The poor things, they never had a chance at anything. They were apprehensive about going to school. When you don’t know something, you kind of shun it.

[My friends] all had a whack at it. Just about everyone had a whack at the mill. If you couldn’t get a job anywhere, they would give you a little one for 25 cents an hour, or something, in those days. Gradually, as opportunities came up, people left town. I graduated from Westford Academy in 1937 and to this day, out of my class of – I think we had 35 or so in my class, a big, big class in those days, (that was the year that Mr. Roudenbush retired) – I don’t believe that there are a dozen of us in town. Most of them are gone. A few are dead. I stayed. I had no other place to go. Along came the war, and when I came back, I liked Westford pretty well. I’ve always lived here. I was on North Street. Now it is 19 North Street.

I remember they worked five-and-a-half days when I first became cognizant of labor. I think they started at six o’clock in the morning. Because they started work at six, they had to get the 5:30 a.m. bus – trolley in those days. My mother worked in Forge Village, and my father worked in the quarry, which is just a half-mile from my house. He would just walk up onto Snake Meadow Hill. He was working there. But it was seasonal. I remember that they would work from six o’clock until 4:30 p.m.

By that time there was a trolley that was going back and forth between Ayer and Lowell. The trolley would be waiting for them at 4:30 p.m. at the Forge Village Square. They all jumped on and went to Graniteville – those that lived in Graniteville. On Saturdays, a lot of times they worked from six to twelve o’clock. So they worked five-and-a-half days. I understand that before that, they used to work six days, too, but I’m not aware of that, myself.

My mother says when she first came they worked those long hours, and I think it was $6 [a week].. But you could buy a loaf of bread for 5 cents. It was scaled, but, for sure, it was small. But if it was scaled down [to compare with today’s wages and prices], the money was worth it.

[Abbot built the ballfield.] What would a Russian family man that had two or three kids and a woman benefit from a ballfield? That was strictly for kids, and for bachelors who didn’t have anything else to do. I think, in a way, Jack Abbot did that to deter crime. Whatever the company offered was strictly for kids and young fellows. I know my father would never be on a soccer team or something like that. Had they offered him something like going to a theater, or something enlightening, that is another thing. But I don’t think that was of any use, particularly for the Russians.

I know when I was a kid and I would go in [the mill] they would have those old English tabs [men to keep tabs on you], and they would really push you to it. The minute they’d see you finished with something they’d give you something to do, even if it wasn’t your job. They made you work all the time. Today I notice in industry, where I work as a security guard, a man gets through with his work and he’s free. He walks around until he finds something else for himself. Not a boss to come up and say, “You do this or you do that.” So the mill workers were pretty well tuckered out by the time the evening came.

They had movie theaters, but what was the good? I remember going to a couple of them. My father always treated movie films and Hollywood stuff as evil. And evil they were, I found, many a time. They showed things like Groucho Marx then, people beating each other over the head like they do in the comedy slapstick on TV today. I think it’s a bad thing for society. The Russians looked at that as something immoral – and not good. So very few of them went. Kids went on most days for 15 cents. They were overpriced, anyway, for a child. They had the movie hall in Forge Village, which is the Murray Hall today [razed in 1980]. Then where the American Legion Hall is in Graniteville, they had a movie hall there. It was all flat seating, flat floor. I remember going to one of them. There are such ridiculous pictures now, but I look back now, and there was no finesse to it at all.

Abbot Worsted had doctors on the premises, and if anybody got hurt in there, they took care of them. At home, in those days, we had physicians. There were several physicians in town, as far as Westford physicians. We had one from Littleton. In fact, Dr. Christie was the one that brought me into the world. I guess he brought everybody of my generation into the world—old Doc Christie. Then, later, Dr. Cowles came in. There was a Dr. Sherman, and Dr. Blaney from Westford. You probably heard that he was a fiery, peppery man, but he was a good doctor. He was a doctor-politician later.

Food

One thing I remember when I was a little kid was that the Russians would go into a swampy area and dig up a certain kind of root when they had a stomachache. It was very fine and stringy looking. It was a little thicker than sewing thread. They called it the rootlets or korinchicky. It’s a certain little flower. They pulled that out, washed it well, and, of all things, they let it soak in a bottle of homemade whiskey. You know the blast? What they called a Polish blast. That would soak and soak. I remember the whiskey, which is made white, would turn yellow from the rootlets. That would stand for months and months. You don’t drink that! That’s just for cures! They would give you a small shot of this root juice. Then you were supposed to sit down, and the stomachache would go away. If a guy comes into your house and you want to offer him a drink – that’s not it. That is an elixir.

They were really good gardeners. I will speak for Graniteville because I was brought up there. Forge Village had the same thing. Up in back of the ballfield, the Abbots would plow up a big plot of land. You had to ask for a plot, and then they would designate a plot for you. Then you grew whatever you wanted. It was way in the woods, behind the ballfield. As funny as it is, nobody ever pilfered anyone else. If anybody pilfered, it would be somebody not related at all – kids or someone that had come through. They grew mostly potatoes, some corn. I don’t think they grew tomatoes much. It was mostly stuff that they could keep in the winter. They’d probably get 8 or 10 bushels of potatoes. In those days we ate a lot of potatoes. It was a cheap food.

To this day I know most of the mushrooms. Every once in a while I read in the paper where people get poisoned. We have eaten mushrooms. My father and mother canned mushrooms. In fact, my father has been dead since 1953, and I think in my mother’s cellar there are still old mushrooms in cans. Not too long ago – my mother died in 1974 – we discovered some mushrooms in a container that my father had dried. They keep, and they add a flavor to a soup. We used to make a mushroom soup, and some of them fried mushrooms. A funny thing – the Russians ate mushrooms in Russia and they never had any trouble. When they got into the United States, somebody sold them the idea that when you cook mushrooms, drop in a clean half o’ dollar – a silver piece. If it comes up tarnished, there is poison in there. I can remember my father going through the ritual of putting in a dime, and then we’d all look for the coin when we ate. We knew there wasn’t any poison in there, because we knew the mushrooms. Apparently somebody that told them that wasn’t sure of his mushrooms. Now when I go up to the library and I see mushroom books, right away I know the Russian names for them. There were other edibles, and some of them the Russians didn’t take because to them, in Russia, a similar one was poisonous. Toadstools – they called them fly killers or mokamore. They don’t call them toadstools over in Russia. It’s a fly killer, because in the olden days they used to boil these mushrooms and kill flies with them. hat’s how they came by it.

I don’t bother [mushrooming] now. My wife can’t stand the sight of a mushroom, and when my kids want to cook, they go out and buy theirs. I don’t see as many mushrooms today as there used to be. You used to have to go into an oak-wooded area, which is sour soil, or a pine area. We used to come out with baskets of them.

The Russians never ate nuts. A little bit as we grew up – they would eat the Christmas nuts. That’s all. My father would. Yes, my father, when we were little kids, would take us down to Gould Road and that area. We would pick up the hazelnuts, pick them when they were green and in their pods. He’d take them home and he’d bury them for about two weeks in the ground. He’d bury them in a sack. That would ripen them for some reason. Then he’d dig them up again. He’d open the sack and the stuff would all fall out, and then they were ready to eat. The New England variety is about the size of a pea. He’d bust them, and we’d eat the little kernels. He would just sit by the hour and flip the hazelnuts to us.

Come spring, and it’s still chilly – we had a big fur coat, a sheepskin-lined coat – and we’d go up into the woods, find a sunny spot, and spread that coat out. It would be in a little lee, and there’d be no wind around. You could hear the wind over the top. Father would pick a few maple saplings, you know, maple whips. He’d cut them off. Sometimes he would make a whistle, or sometimes just a peg. But just the fact that he peeled that skin off, made that wood so nice and white, it was very attractive. We’d prize those for the longest time.

I can remember my mother making our own macaroni. All the Russians did. They’d see it at the store – store macaroni! They would roll their things [ingredients] out just like they do a piecrust. They’d lay it on a big paper on the bed, or anything flat, and let it get hard. When it got so that it was like a sheet, then they would roll it up and chop it fine, and that was macaroni. They made a macaroni – I don’t know what you would call it, but they used macaroni – they boiled it in water and then would add milk. It was like a porridge. It was good tasting, and we didn’t know the difference. We always thought, “Macaroni! We were going to eat macaroni”

They lived simply, that’s the whole thing. When they were through eating, they never had to have pie and cake and coffee, like you and I. They got through eating and they had a drink of water, and that’s it. For the longest time I did that. It’s my wife that’s spoiling me. She gives me the goodies, and look at this – look at my stomach!

My mother and, I guess, most of the Russians made what they called a bean-potato soup. It was out of this world, now that I’ve tasted other soups. A beef soup they’d make, and pea soup – pea soup was their own. The pea soup they would make would be out of the very little peas, those little hard peas. I remember my father used to like to take those hard peas, put them in the oven, and roast them. Then we’d eat them. Gee, they’d almost break your teeth, but they tasted good. Oh, cabbage soup! There was always cabbage, with a little lamb in it, or other things. They’d shred the cabbage up. There were many soups, because in those days, always before an election, the mills went slack a little bit.

I still have my father’s [basket he wove from a willow tree]. Yes, willow trees, and alders, certain types of alders. In fact, I don’t know if it’s any good for historical value, but when the museum gets done, I’d like to donate it outright to the town, if they’d like it. I still have one that he made back in the ’40s. They used those when they harvested potatoes. It would hold a bushel, some of them 2 bushels. He made it here. He gathered a lot of those willows and things along the old railroad car lines, near the swamps. The car lines went through the swamps. He’d take a walk one day, say to Forge Village, on his way home. He’d bring home an armload of willows. That’s the way that he did it.

Some of them [made fishnets too]. My father never made them. In those days it was illegal to make fishnets. The Fish & Game Department frowned on it. But the Russians didn’t know the difference. In Russia you could use fishnets. When they came over here, there were two or three – I don’t recall the guys anymore that made them. “They were good,” they said. I just saw one off-hand one time when I was a little boy. When the fish came up to spawn, they would put them in, and they’d come home, I suppose, with a bag of fish. That was discontinued back in the ’30s, after a few men got caught and paid a fine. They passed the word around, “It’s no good!”

Later, after [my father] became a citizen, and licensed, he got himself a line and went all over the place fishing, in his own little way. I guess he just liked to fish, that’s all.

Trains, Trolley and the Automobile

My father worked on the railroad for a while. I believe it was in 1929. Just before the big crash, Stony Brook branch was double-lining their railroad here. So he got a job on the crew, because things were slack everywhere. He worked from North Littleton down to, I would say, Chelmsford. They double-tracked it from Ayer to North Chelmsford Junction. It was a lot of work. I remember they had pile drivers for when they had to widen bridges- -at Stony Brook, for one, in Graniteville near the railroad station. The railroad made quite a history in town, and [elicits] nostalgia. To this day, I like it. Those big locomotives used to come hissing by..

We never had a horse. My father never got a car until 1930 or 1931. It was a big Hudson, I remember. In those days, the street railway ran every hour. It went down to Greig’s Corner where the old Grodno store is now. I remember on the half-hour it passed Greig’s Corner. We’d wait there, if we wanted to go to Lowell. If we didn’t want to go to Lowell, when the car went down about a mile further toward Lowell from Greig’s Corner where there was an interchange, the conductor from Lowell would enter the switch – first one, and then the other one. Then he’d just switch cars, and he’d go back again. We’d call that the switch. In about 10 minutes the car came back again. You could get on it to go to Forge or Ayer, or wherever you wanted to go.

Most of the Russians, in order to save money, father and mother worked. My mother was sick a lot, so that meant only one paycheck. You don’t get very far. Secovich and a fellow named Peter Worobey in Forge Village, they had cars pretty early. Also, the Grodno store had a Ford truck, one of those fruit trucks, a Model T with curtains on the sides. Whenever anyone wanted to go in a gang they’d just put benches in there, and they’d take eight or ten people and go to church in that. It was especially ethnic that way.

My father made wine one time. He made two barrels, one of elderberry and one of rum cherry, and he mixed the two. In those days, friends would just come and you’d break out a bottle of it. Everybody used to like to come to my father’s for the wine because they liked the taste of it. It was a great combination. But as far as booze, they had to make it. Everybody else was making it. Some of them sold it, and they made extra money on that, too.

I think it was due to political reasons. The Russians would say, “Well, after the elections, you know.” It got so that everybody knew that after the elections business would start up again. I think there was some kind of psychology to it that if the improper party got in things wouldn’t run good. Whatever party got in, the mills picked up again. Things were rough. You couldn’t go on unemployment in those days. In fact, my father was called what is equivalent to a Communist today, because back in the early ’20s he dared to say that someday when things get slack and people can’t make it they are going to have to have what is now unemployment. People said, “Well, you’re talking like you are a Communist!” In those days there were no Communists. It was something else they were called – anarchists or something like that. But it all came true, you see. So my father was really ahead of his time, but he sounded off about it. So that made him an alien.

Let’s see, we were talking about soups and foods. My mother used to make a thing they called a foranikee. It was like a cheesecake, a cheese turnover. It’s a special Russian thing. I imagine some of the other Russian women did, too. Oh, yes, and they made what they called overalls. They were made out of very light flour, and they twisted them. Then they cooked them in deep fat and put them in powdered sugar. They have some here in America now, but they never compare. They are very light. You take them and they break – very crispy and nice. We prize chicken and turkey – they had eggs. For Easter, they always had a lot of eggs.

There is mashed potato—in Russian, called carsha. You know, the Russians come from a big area. Terminology and pronunciation for a word in one area, like around Grodno, would be different a couple hundred miles away. But the ones I’m talking about, these were Grodno-oriented people. So they all spoke the same, and they didn’t speak pure Russian. It’s sort of a pigeon Russian. One thing about it is that the Poles mixed in pretty freely with the Russians. They came right around the same time. There were quite a few Poles. Also, the Lithuanians—there were maybe a dozen families of Lithuanians. Some of them have died off. They all died out, but their offspring are still around. Some of them left town. The only way I can tell is when I pick up the directory of the town and see certain names – it harkens back. A lot of the Russians that were in town have left, too. You meet them once in a while somewhere.

There were 42 Russian families. I don’t know if today you can call them Russian families. Some of them intermarried, and I wouldn’t even know where they are. I can still remember a few of them, like the Secoviches. There are two or three families of them. As they [Russians] got kids—there were four or five or six of them in the family- some of them moved away, and some stayed here. So I really wouldn’t know today how many are around. I meet them and I know, but I would have to sit down and go over, mentally, the whole map of Westford and think where they are. Some of them intermarried and divorced. Some of them have Americanized, and they’ve lost their ethnicity.

They never asked for anything and never got anything. They worked hard for what they got. There is one thing that I have to say. Most of them own property today, which some of the Americans, I notice, who had better pay and better deals, never did. I won’t name the person, but there was a boss in the Forge Village mill one time, and he hadn’t died a month and the wife -they were living in a company house – and the wife went on welfare. The bosses made good money in comparison to the workers. But you never hear of one Russian that went on welfare. They came here with the idea that they were going to make a living, and they made one. They earned their respect. [When] my father died he left us a house which is worth maybe $35,000 to $40,000 today [1977]. We are going to sell it. My sister is living in it. My mother died.

They would help themselves. They’re something like Jews. They will help each other. No sir, nobody ever asks for welfare. Later on, when other nationalities put them wise, I understand one or two tried it during the Depression, but they [the authorities] checked the bank and found some money in it. Even if they were out of work, the Russians had money. They were very thrifty. So I don’t believe there was even one that went on welfare.

I have pride in the fact that I’m an American, and I’m dropping off my ethnicity to the extent that I think there’s a time and a place for it, and this isn’t it. I think the quicker we intermix, become an American, that’s the way it should be. Don’t say American, I say United Statesman, because an American can be a Canadian or a Mexican. We don’t have to equate with them. We are our own breed—United Statesmen.

I’m glad that I went through those times; I think it taught me thrift. Like today’s kids, when they grow up they expect all this stuff. When we were kids we were poor, and we didn’t know it. We cared less. My father rarely bought us toys. In fact, most Russians never bothered. They’d buy a few substantial toys. My brother and I were creative, and we’d make our own little crude locomotives. My father would buy us a hammer – a small toy hammer, not too small, but a good size. Or sometimes when he went to work, we’d sneak his out. We’d get pieces of wood, and we made locomotives and cars. Our yard, it was never neat like today’s yards. We had holes dug in it, in the sand banks and gravel banks in there, and we played. But my mother knew we were in our yard. We didn’t have to go to any ball field to be entertained. There were no ball fields for kids. Those were for grownups!

[My mother] embroidered. I think we have some of her work. In those days they would embroider the end of the pillowcase, or they would make a lace and sew it to the end, and place a fancy-colored pillow inside. At one time, it was the Russian’s mode to make portieres. They would crochet them or weave them. Later, they got beads. They went up into Lawrence, into this novelty shop somewhere, and they’d buy tons of beads. Then they’d make portieres, and they’d be hanging there. You don’t have anything like that. Later, somebody thought up the idea of cutting the two legs off the clothespins and, on the top and bottom, putting in little screw eyes for tiebacks. Socks and stockings. When I was a little boy, my mother bought a sock-weaving machine from this family down the street. There are remnants of it somewhere in my mother’s attic now. It had cylinders, and they had these little needles. Once you had it all set up, you turned it, and it would go around – zing, zing, zing – and it would weave. It would make socks. You could make rows and rows, but when you came to the heel and toe, there was a certain procedure my mother would use. She made enough hose or stockings for all of us. People would bring yarn to her, and for a small fee she would do that. Maybe for 25 cents a pair, she would do them. But there was a lot of work to it. She sat up nights, long into the evening, working on the machine, I remember.

All the Russians made sweaters for the Red Cross [during WWII]. There were a lot of them. I remember them sending me a sweater. On it was made a V with a da da da dum for the musician. I have that sweater to this day. It is a nice heavy sweater. I don’t know whether the Abbot Worsted Company donated the yarn, or where they got it. I was in the service. I came home one day and they had big boxes of them. They were making, I think, scarves and hats, too, and mittens. They made mittens. I remember my mother being the chairlady of the organization. My mother was always a little brassy that way. They’d run raffles down at Grodno’s store. See, that was their own hall, so there was no tax or no rent. They ran something just about every week, and they raffled off something. The money they’d take in, they’d send either to the Red Cross or towards the war effort. They were very active all through the war that way.

This interview was conducted by June Kennedy in 1977 and edited with June’s permission in 2019 for the Westford Museum and Historical Society winter discussion group. Russian words are spelled according to the best recollection of the interviewee.