– BILLY –

William Joseph Kelly, known as Billy, was born in Oldham, England. As a teenager he lived on Bradford Street in Forge Village. Within a few years of his arrival in Westford, he married Sarah (Sadie) Smith – July 22, 1914. She was born in Keighley, England. According to niece Kay Teague, this couple lived first on Pond Street, and later Orchard and Smith Streets, before buying the home at 2 Coolidge Street where they lived in 1974.

During this time the couple raised their children Bill, Jr., Frances, and Margaret (Peggy). Billy Kelly was accompanied by his niece, Veronica Sullivan, for this interview. His pleasant manner, Lancastrian accent, and true sincerity add a special quality to his story. He loved his Forge Village.

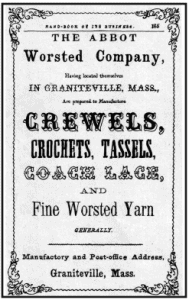

The Abbot Worsted Company

My name is William Kelly. I live in Forge Village, Massachusetts. I was born in the year 1891. I’ll be 87 next year. I’ve lived here practically all my life – married 63 years. I’m of Irish descent. One of my parents was from Ireland. My mother came from Wales. I came here in nineteen hundred and twelve. I went to Chicago first in 1911, and then I came here. Been here ever since.

I was an overseer in the Abbot mills for 46 years. In the first place they made carpet yarn, which was a coarse wool from a sheep from England and Scotland. They stayed on that until about 1916. That was the year before we entered the First World War. Then we went onto a finer grade of wool. Some of it was half blood, some of it quarter blood. The full blood was a merino sheep, which when paired with other sheep would be half blood, and then another pairing after that would be quarter blood. Then they went into makin’ yarn for different companies, and at one time Abbot Worsted Company was the largest manufacturer of sales yarn in the country. Some claim it was the largest maker of saleable yarn in the world.

Then they went on from there and they started makin’ knittin’ yarn – a lot of it – which was mostly quarter blood. The bulk of the knitting yarn was sent to Bernhard Ulmann in lower Manhattan, New York. Ulmann sent the yarns to Providence, Rhode Island to be dyed. He had sweaters made for New York sales. Some yarn was sent back to Abbot Worsted Company, where office manager at Forge Village, Ed Hanley, had his sister, Kate, sold it as Hanley Yarns at the Prescott Tavern in Forge Village at least through the fall of 1959.]

Then they started branchin’ out into mohair. Mohair was a goat. And they got it from both Turkey and Texas. [The automobile upholstery made by the Abbot Worsted Company in the 1920s was mohair. Wool was added to the mohair in the 1930s to make the fabric more comfortable.]

Veronica: I’ll tell you something. My husband and I were out in Chicago at the World’s Fair in 1934. He was looking around at something and I was looking around and I said, “Dad, come here.” And what was in the book but the picture of Abbot’s tower and Abbot’s mill. It seemed so funny to see that picture out there in Chicago. It had the bell in the tower. There’s a weathervane. It’s a sheep. I said, “Look, we’re right back home. Here’s a picture because Ford bought all their mohair for their cars from the Abbot Worsted Company.”

Billy: Ford, GMC, and Sears, Roebuck.

At first, the girls used to take care of 100 spindles on each side [of the frame], and that kept on until we branched out from carpet yarn to other yarns. Then the machines were turned over to what they called a cap spinnin’ frame. First it was a flyer which you could only run at 2,000 rpm but under the cap you could run them 5,000 or 6,000 rpm. Then they went from 200 spindles to 400 spindles per girl. Then they got into this mohair, and different yarns, and they changed from cap to ring spinnin’ and they could run that at 7,000 rpm.

In 1914, the floor help or the laborer got 10 cents an hour. What they called the doffers got $5.95 per week, and the girls that was runnin’ the frames could make about $9 or $10 a week. Then after they got more speed on the frames, of course, you could make more money. In the name of progress, they brought in these efficiency concerns. After they got through analyzin’ everythin’ and takin’ tests and everythin’ else, they went from 400 to 600 spindles – one girl.

And also, if you want me to mention this, they had a one-day strike, protestin’ against the efficiency. The labor load went from 200 to 600 spindles in steps. That last step, when they had the efficiency men there, they went from 400 to 600. They didn’t put anybody out of work. The employees went on strike because of the workload. They had to step it up themselves.

At one time 14 was the age you legally were supposed to be allowed to work in the mill. Before that you couldn’t go in, supposedly. But they used to slip ’em in, and when the factory inspector came ’round we’d put ’em under the frame or someplace.

[The wool] went first to the washroom- the raw material – then it was dried. Then it went to the sortin’ room, to sort the different qualities of the wool. From the sortin’ room it went down to the cardin’ room. Some wool was carded; others was just combed. It went to the cardin’ room before the combin’ room. Then we went to the final wool process. We weren’t a woolen mill. We were a worsted mill.

Now with the worsted the short fibers are taken out, with the woolen [the short fibers] left. The principle of the thing was to get different operations to draw the fibers out. From the combin’ room it went to the drawin’ room where they called the machinery there, all in a line – they called it the drawin’ set. Gill boxes – called candle boxes first – was all piled up at the back of the room. You could make a seven-drum rovin’ or a ten-drum rovin’ or anythin’ like that, different weights, whatever you wanted.

It then went through the drawin’ room to the spinnin’ room. That’s where the fiber was drawn out to its longest length. The spinnin’ room consisted of a back roller, which was slow, to a front roller, which was fast. In-between there was what they called carriers. It was three lines and the fiber went from the back roll, which was rollin’ it, to the front roller, which was pullin’ it out. That was the principle, and the distance between the front row and the back row was what they called the draft.

And then it went to the twistin’ room. In later years it went from the twistin’ room to the windin’ room, which was tubes or cones. And when they were shippin’ it out, it would go down to the spoolin’ room – could run up to 500 ends through there. A girl fed it as it was comin’ down – she was watchin’ for the bad work as it came down. She could stop the frame and take out the bad work. That was warpin’. But it went to the spoolin’ first, then it went from the spoolin’ to the warp. They used to ship it out in warps then, unless someone asked to have it shipped out on spools. But there would be anywhere from 400 ends to 600 ends on these big warps [balls].

We didn’t make any cloth at all. It was all yarn. That went to some mills that was makin’ cloth; it was then put into the looms when it got to those places. That I can’t tell you much about. I was makin’ the yarns. [Abbot’s weaving yarn was hauled by Wright Trucking Company to companies in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and to Shelton, Connecticut.

The overseer has all the responsibility in the world on him. Someone of supervisor capacity had better pay. (Laugh) One time there at the end, when they gave you both shifts – the first and second shift – you had to take care of ’em both, which was really bein’ on call. If anythin’ durin’ the night came up, they’d call you at the house. Two shifts at the yarn mill and three shifts in what they call preparin’ for the spinnin’ room – combin’, cardin’, and drawin’. Before it got to the spinnin’, it was called preparin’. That’s what it was called.

The English and Irish could get any job they wanted because there was a lot of paperwork attached to it. The women were more apt to work at spinnin’, twistin’, warpin’, spoolin’. And they were pretty adept at tyin’ a knot. Oh, they could tie a knot, and you couldn’t see the fingers goin’.

Veronica Sullivan: I was born in England. My mother was born in Ireland; my father was born in England. I’ve lived in Forge Village since 1909, most of my life.

I only worked for a little while in the mills. I worked about three years when I was young. I worked as a doffer for the twisters. I worked the first shift. In those days it used to be close to 6:30 a.m. until noontime, and until 11 a.m. on Saturdays. Then lunch was three-quarters of an hour. We went home or brought our own lunch pail. Around 7:30 or quarter of eight we had what you would call a morning coffee break. They wouldn’t let you stop the frames, though. You’d have to get up if the work run down. You’d have to get up and tie the ends.

You had to eat your lunch on the fly – not a complete lunch break. Not like they have today. Just before I came you used to work all day Saturday till three o’clock. Used to work 54 hours when I came there.

Billy: All down-to-earth people. I have good friends amongst ’em now. I wasn’t one of those bosses they hated. They all recognize me now. [Identifying people in a photo] I know everyone of ’em. Old man Weaver, Kavanagh . . .

J.C. Abbot. When he went everythin’ seemed to go – Jack Abbot. [John, called Jack, Abbot was treasurer and general manager of the Abbot Worsted Company until his death in 1934.] [Jack Abbot] did so many good things. I know he used to ask me once or twice at Christmas time, “Billy, do you know anybody in the village or in the town that’s up against it?” He was very charitable. But after the strike, he changed altogether. He never thought his people would go out on strike. It certainly did hurt. They went out in the mornin’ and came back the next day. It was before the Depression.

I’ll tell you what he used to do. The houses in those days – course they didn’t have a bathroom -but they were nice houses. I lived in a cottage. When there were slack periods, when you only worked four days or somethin’ like that, he’d only take half rent and the rent was only $6 a month in those days. Five rooms. Nice rooms. He’d only take half rent and you didn’t have to make any of it up, either. He was a generous man. When he soured, everythin’, everythin’ seemed to go. I think he was hurt so much when the people went out on strike. And then he had two sons. Bobby’s livin’ today – I’ve never heard of him dyin’. [Robert Fletcher Abbot was born in 1904.] The other son was up and comin’ and “get out with the boys,” you know, and all this. Bobby – [Jack] told me this himself – he tried to get Bobby interested in the company.

Veronica: Was the second son’s name Fletcher?

Billy: Fletcher, you’re right, [John Fletcher Abbot, but he was called Fletcher]. And [Mr. Abbot] put Bobby a little bit in charge of the office. (Laugh) Bobby would come down with his rosette in his coat every mornin’. He went out to Hollywood and got mixed up with the actresses there, you know. I was workin’ one night about two o’clock in the mornin’ and I went down to the boiler room. In those days you weren’t allowed to smoke in the mill, but the overseer had the advantage of goin’ down to the boiler room to have a smoke. So I went down this night to have a smoke and I saw this hat was on the steps as I got into the engine room – the boiler room was here, the engine room there. I couldn’t resist. I saw this hat on the floor, so I give it a boot right into the piles of coal. The fireman says, “That’s Bobby Abbot’s hat,” and I said, “Come on, what are you talkin’ about?” And the fellow went over, as he was talkin’ to me, and got it. He didn’t put it on the steps. He put it on the floor, and I booted it again back into the coals. Just then one of the boys that worked for me came down and said, “Mr. Kelly, Mr. Abbot is up in your department.” I went up and he had these two Hollywood people – actresses, you know. “Show ’em around, Billy,” and this and that and the other. And that’s the kind of a guy he was. He never took over the mills.

Fletcher died a young man [1898-1916 from polio]. I think that’s when J.C. started takin’ an interest – takin’ hold of sports. I think it was to get out some. I understand that Mrs. Abbot was a Christian Scientist, so they didn’t have a doctor for the boy. That’s what I understand. He couldn’t be saved, anyway.

Over the years, there have been two Abbot houses where the post office is now [at 45 Main Street – today the Northern Bank & Trust Company]. Jack Abbot’s, was the one that was torn down. [The Mansion, razed in 1941. The original Abbot house had been moved to 44 Boston Road in 1871 so The Mansion could be built in the site.] He was a fine fellow.

[Abbot] had been closed down for about a year [when Murray Printing came]. That was in ’56.

The Abbot Worsted Soccer Team

I’ll tell you how soccer was in those days around here. Boston had a good professional soccer team. I took Jack Abbot down to see Bethlehem Steel play against Fall River. Of course, I was the only fellow in Forge Village – not that I’m braggin’ – who could really play soccer at the time. He saw soccer as it should be played that day. So comin’ home he said to me, he said, “Oh, Billy, what are we going to do? I want a soccer team. I want a soccer team.”

Some of the professional teams, they paid ’em without workin’ there. They were workin’ someplace else. J.C. Abbot wanted everybody to work here. In the meantime, I wanted him to go up to American Optical Company in Southbridge. They were gonna get a good team together. I went up, my wife and I, to set us up. So we went up, and Kershaw was workin’ there at the time. For two or three weeks I met Mr. Abbot in the Village and said this Kershaw was a good man and all – so we hired Kershaw [as manager of the Abbot soccer team]. But he only stayed on one year. He got a little too big for his britches and was tellin’ Mr. Abbot what to do.

He called me one day and he said he’d released Kershaw and I would have to take it over. So I did. So that’s how it got started. I checked two or three people in England that I knew at that time – I’d only been away for probably about 12 years. Now this Bob Perry that’s on there, I had him in the house eatin’ his supper, and his first cousin was down in Boston waitin’ for him. I went down to meet him at the boat and brought him up. I wanted Bob to get him to sign the papers, you know – sign the papers. This McDade turned out to be one of the best players in the country. Billy was Irish International before he left Ireland – Belfast. So that’s how you got ’em.

[Mr. Abbot] used to come to my house on a Sunday mornin’. I was the manager of the soccer team. He was a poor loser. I remember one time we had to play at Fall River. I played, too. That was from about 1919-1926. I was the only man that wasn’t imported.

There have been as many as 400 people leave Forge Village on a train to watch a game in Pawtucket. Spectators. Do you know what they did? They got permission from the State to work overtime a half-hour each night, so they could be shipped down on Saturday mornin’. Got a special train – two or three special trains. Went around to Holyoke, Fall River, Pawtucket, different places, you know.

We went down every Tuesday afternoon and every Thursday afternoon to do the trainin’. Now the first day Tuesday’d be calisthenics. Thursday it would be ball practice. It was taken out of the workday. You were paid for that instead of workin’ in the mill. We had wonderful protection. Free doctors. Free hospitals. Soccer is a great game for gettin’ your knees hurt, you know. Quite a few had the cartilage taken out. Joe Priggart had both the inside and the outside cartilage taken out.

Will you look at this scrapbook? These are all clippings from The Boston Globe. George Collins was the columnist for The Boston Globe. You see that? That says that Shawsheen – the American Woolen Company – beat us 2 to 1 in the Eastern final. Now this Cup when it starts out, it’s from ocean to ocean, all the soccer teams. In those days probably 1,800 entered the Cup competition. But they played it in sections – the West, the Middle West, the Pacific States, East – until they get one in each section. That’s the finalist. We were East. And when you were beat, you were out. It was a knockout competition! Didn’t get another chance if you got beat. We were the last two in this section and they beat us, 2 to 1. They beat us. And I’ll tell you it was a disappointed crowd. About 2,500 people there at that time. It was played in Shawsheen. A professional team, no doubt about that.

We got to the finals – Eastern finals -three times. Three times the bridesmaid and never the bride. We got beat every time in the finals. We played soccer up where the field is now – the Legion Field – in Forge Village. The people that laid that field out laid Braves Field out in Boston. That is one of the best-drained fields. They used to say – even the visitin’ players said it – “If you couldn’t play soccer on that field, you couldn’t play.” You got knocked down, it was just like velvet. You’d come up, you wouldn’t be hurt. Beautiful field. You know in soccer you have to jump high to get the ball, you know, with your head. You understand that? You can only use your head and your feet. Sometimes when you’re up in the air, you know, they can do a job on you if they want to, but you get down there, and you just jump right up.

In 1921 or ‘22 or ‘23, $35 or $40 was quite a wage for a week. Well, J.C. paid them $35 a week in the mill for doin’ nothin’, as long as they showed up. In those days “Jule” [Julian Abbot] Cameron was the president of the Company [1900-1934]. J. C. was the chairman. “Jule” Cameron would come ’round every mornin’ to every department and these fellows were supposed to run and hide when he was around. I’ll give you a funny incident. One time a fella not in these pictures because he only stayed with us about three weeks – he stood there with a piece of wood about so big in his hand, and a penknife. Instead of duckin’, he stood there and “Jule” Cameron saw him and said, “What are you doing?” And he said, “I’m making a boat.” (Laugh)

I’ll tell you this. I was the manager and it was a headache. He gave ’em a house, mind ya. He put a house to one side for ’em and put two women in housekeepin’. All they had to pay was $5 a week, board and room.

Ice Hockey & Baseball

The hockey rink was right across from my house – from the Elks Club [2 Coolidge Street]. And do you know that the rink was only a few feet shorter than the [Boston] Garden? It was nice for me. I could go out on my porch and watch it. It was so darn cold, you know.

The Arrows was the baseball team. I don’t know if the hockey team had a name. Dartmouth played there. Harvard played there. Not all the time. Dartmouth and Harvard played there, not in the league, it was kind of a friendly thing. “Sandy,” “Sandy” [Alexander] Cameron [Julian’s son] was very interested in hockey.

Soccer was in Forge Village, baseball in Graniteville. Mr. Abbot decided that we had a very good team in Forge Village, a good baseball team, and that he had a better team – at least he thought he had a better team, in Graniteville. I was really in on this. He got confused. In fact, he got a little vexed about it. And so he said, “What are we going to do about it, Bill?” I said, “I’ll tell you what.” I was on the committee of the town baseball team, not connected with the company at all when it started out. “I’ll tell you what we’ll do. We’ll challenge you, Mr. Abbot.” We had a town team and he had the Abbot Worsted team.

We were called Forge Village. Anyway, we played ’em. Mr. Abbot’s team almost murdered us. So he decided, then, soccer in Forge Village, baseball in Graniteville – and “I’ll help you both out.” So we played a couple of years, I think.

I’ll tell you who kept the record of all the games. I’ll tell you how thorough Mr. Abbot was. He had Miss [Gertrude] Fletcher in the office – and she was a big shot in the office – he had her keep all the records of the soccer and baseball games. I have another [scrapbook] on baseball if you’d like to see it. At the time they were closin’ the mill down, she sent for me over to Abbot’s and she said, “Billy, I want you to have these, if you’ll have them.” She said, “They’re no use to me.” I said, “Oh, well, give ’em to me. I’ll take ’em.” So, that’s how I got ’em.

Entertainment in the Village

The minstrel show was an annual event for about four or five years. Mostly folks from the Forge Village mill. If you’re goin’ to say anythin’ about the minstrel show, I think Jimmy May ought to get a lot of credit for that. He organized it. He was a musician. He trained the chorus and they had a damn good chorus.

Veronica Sullivan: They gave us two days off after the First World War ended.

Billy: The parade took over the town. They organized that parade, I bet, in 10 minutes down in Forge Village. (Laugh) We went all around the town . . . went crazy, picked up people along the way.

Veronica: I had shoes that laced, you know. I didn’t have time to lace them as we went out in the morning to work. By the time we got to Westford my feet were frozen. I stood on the Common and laced the shoes on the Common. The bandstand was there then. People pulled you into their houses; they had this little box lunch for you.

The Forge Village Fife & Drum Corps went down to Lowell and different places. [Members of the corps from a photo are Jack Edwards, Billy Dureault, Jack Baker, Bill Baker, George Shackleton, John Sharpe, Fred Davis, George Weaver, George Wilson.] The Abbot Worsted Band uniforms were blue, I think – a solid color. They gave Westford Academy some instruments when this band broke up. The instructor of the band, the leader, he was from the Masons in Boston and had a big reputation for music. Harlow, his name was Harlow.

The Train and the Electric Street Car

Back in 1921, I’ll tell you what. We’d been down to Graniteville to watch a baseball game and the other team didn’t show up. We was walkin’ back from Graniteville to Forge and we looked over and saw this freight train comin’ along and then we heard this crash a little while afterwards. You could see the cars bucklin’, even as far back as we were you could see them bucklin’. It was a long train. We went on down to Forge Village. Two or three of us climbed up on the engine. It leaned. The engine didn’t go all the way over; it leaned against—there was a loadin’ platform there from the warehouses for the company – and it just leaned over, like that. Somebody said, “There is somebody in the engine there.” Couple of guys climbed up there and I could see this hand stickin’ out. He was dead. Then they told me – my brother, Jimmy, saw this fellow was walkin’ down the yard lookin’ for the first-aid room. He’d been scalded from the hot water – it was a steam engine. Anyway, they went down and got him into the ambulance. He died. There were two killed. Every night, for about four or five nights that week, we were down watchin’ ’em get the cars back on the rails. I remember that quite well. That was 1921.

Veronica: I know we had a nine o’clock curfew. When we were kids, growing up, we had to be in the house before that nine o’clock mill bell went. Your parents said, “You be in here when the bell rings.” In the morning, when you started work at 6:30, the bell rang at 25 after [six] – what they called the first bell – and that gave you five minutes to get in, and then they rung the bell at 6:30.

There used to be three trains that went by in those days – mail trains. One would go up and one would go down, and every night you’d go down for the mail at the post office and wait until the mail was all sorted, and then that was it. That was your pleasure for the evening. You either went home then or you’d go to a friend’s house. It was a lot of fun.

[ The post office was in the big Prescott Tavern that they tore down.] But it wasn’t there in the beginning, no. It was over where the Whistle Stop is now, that liquor store or family shop or whatever it is now on the corner. [Pizzeria Presti, 2 East Prescott Street] Abby Splaine, she was the postmistress then. Josephine Connell was postmistress when it was in the tavern.

I didn’t like to see the tavern go [in 1976]. I didn’t like to see it go down – it was so old. Coaches used to stop there, let the people off, you know, the old coaches. My sister, her first apartment was down in that building [tavern] you were talking about. Kate Hanley had a store there. Everybody did business with Kate. When you’d pay your bills once a week, Katie Hanley would give you a bag of candy – for paying the bill.

The trains used to run quite often – the electric cars .

Billy: Very convenient way to get down to Lowell for 15 cents.

Veronica: In those days they had three telegraphers in the depot: morning shift, middle shift, and late-night shift. The girls used to work there in those days, giving messages for the trains, because they only had the one track, you see.

I went once a month because that was all I could afford. I had to save up my money, and, by that time, I’d have 55 cents. I’d go to the movies, pay 10 cents for a pound of fudge, and then I’d look around to see if I could buy anything – a hamburger, – but never had enough to buy it. I always came back broke.

Billy: Go down to Lowell, go into a show, get a little lunch, a hot dog, a hamburg, and come back with about 20 cents out of a dollar. (Laugh)

“Sportiest Town in the Nation.”

At one time I’d say that Forge Village was the sportiest town in the nation. They had hockey. They had soccer. They had bowling alleys. They had baseball. They had movies. Tuesday and Saturday nights they had movies. People who wasn’t here at that time couldn’t realize what a place this was. There was everythin’ in Forge Village. Anythin’, in that little Village. They had it then. Glorious! Oh, it was a sporty little town. Forge Village was the best of the town, I think.

I’ll tell you what we used to do in the wintertime, especially the ethnic groups, like Scotsmen and Irishmen. All the neighbors had a little party every Saturday night – in a house with a case of beer and a fifth. You’d all put a 50-cent piece down before expenses, so the woman of the house didn’t have to put anythin’ out – all winter. Then at the end of the party, somebody’d get up and say, “Whose house is it next week?” And it’s, “Well, it’s my turn next week.” And in their turn they’d go ’round in different houses. If you were sick they’d have the chicken soup there, and everythin’ else for you. Billy: I’ll tell you somethin’. I don’t know if it was a good thing or a bad thing. But you’d order a case of beer – you could get a keg from Billy Murphy in Lowell – and for a dollar and a quarter it come up to the Village on the train. Then you’d have to go down to the depot to pick it up. After a while they’d forget to send the cases back and they’d be piled up there, and they’d have to send somebody else to pick them up. That was before Prohibition.

Veronica: I don’t know about the parties he’s talking about – I was very young. But the ones I remember, they’d have them, like he says, Saturday night. The proceeds that they took up in the dish – they’d put only a quarter, whatever they wanted in it. Money they took up would be sent back to our pastor in England to help build his church, to help him with his church.

Peddlers used to come from Lowell with sacks of clothing on their backs. They’d get off the electric cars and go around knocking on your doors and see if you wanted anything – kind of persistent. They’d take out their wares and show them to you, and if you felt like buying, you would. Very reasonable. They came for years.

Veronica: [Nabnasset] was Brookside then.

Billy: There was a rivalry.

Westford, uptown, never seemed to join in. They looked down on the people that had to work for a livin’. Some of the young fellows used to come down to Forge Village and Graniteville to get the fun and join the teams. There were dances uptown – we’d walk to Town Hall on freezin’ cold nights.

You used to have to walk up to the Academy from Forge Village to go to school. The children did. I went to “Abbot’s Academy.” Now if they have to go a hundred yards, they have to ride.

When we came here first, we were the only ones in the town. Look at it now. Must be 14 to 15,000 in this town now. We’ve seen a lot of changes. And they’re still buildin’

Veronica: You go to church now and, two pews ahead of you, you don’t know anybody. This year a fella came from California to visit his sister and he saw me in church and he shook my hands and he says, “Veronica, I don’t know anybody,” and I says, “Jimmy, I live here and I don’t know anybody.

From June Kennedy’s book Westford Recollections of Days Gone By; Recorded Interviews, 1974-1975, A Millennium Update (2006), pp. 207-220, edited for the February 2019 Museum discussion group with June’s permission.