By Leslie Howard

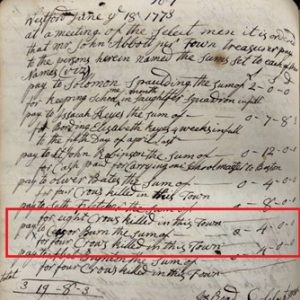

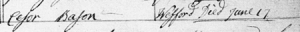

Caesor’s beginnings are unclear. Through the historical record, there are several discrepancies in the spellings of his name and three possible last names. He’s been Caesor Burn, Caesar Bascom, Sezor Bason, Caesor Bason, and Cesor Bason. This last one being the generally accepted version of the name. The first mention of Caesor is when he was paid 4 shillings in 1773 for killing four crows in town.[1]

Caesor’s beginnings are unclear. Through the historical record, there are several discrepancies in the spellings of his name and three possible last names. He’s been Caesor Burn, Caesar Bascom, Sezor Bason, Caesor Bason, and Cesor Bason. This last one being the generally accepted version of the name. The first mention of Caesor is when he was paid 4 shillings in 1773 for killing four crows in town.[1]

Through some research (see Leslie Howard’s Once Known: A History of Slavery in Westford, MA and William B. Prescott’s Taxation of Slave Owners in Colonial Westford), it is assumed that Caesor Burn was enslaved by James Burn, a potter who lived near Rattlesnake Hill. In tax records, Burn was assessed for a slave in 1752 and 1768.[2] Burn died in 1771. There is no record of emancipation for Caesor. Though not a landowner, Caesor immersed himself in Westford’s community, and among other things contributed to keeping the crow population down and participated in the town’s Militia. Despite laws against enslaved and free Blacks owning guns and participating in the militia, Caesor was a Private in the Second Foot Company of the Westford Militia. Often, rules about military participation were softened during times when there might be an impending crisis, such as the early 1770s in Massachusetts. The Militia Captain was Jonathan Minot. Along with the other members of the Westford Militia, Caesor answered the Lexington Alarm on the morning of April 19, 1775 and fought the British Regulars on the Battle Road in Lexington.

Caesor officially enlisted in the Continental Army on April 26, 1775 for an eight month period. This was in Captain Abijah Wyman’s company in Colonel William Prescott’s Regiment. Colonel Prescott’s regiment constructed the redoubt the night prior to the Battle of Bunker Hill. Prescott described the scene to John Adams, “We arrived at the Spot the Lines were drawn by the Engineer and we began the Intrenchmant about 12 o’Clock and plying the Work with all possible Expedition till Just before sun rising, when the Enemy began a very heavy Canonading and Bombardment…Our Ammunition being nearly exhausted could keep up only a scattering Fire. The Enemy being numerous surrounded our little Fort began to mount our Lines and enter the Fort with their Bayonets, we was obliged to retreat through them while they kept up as hot a fire as it was possible for them to make we having very few Bayonets could make no resistance”[3]

There is an account in Hodgman’s History of Westford, where he recounts the story “on good authority” that in the battle, Caesor found that he was almost out of his powder and putting in his last charge said to himself, “Now, Cesar, give ‘em one more.” He fired his musket, was then shot, fell back into the trench, and died.[4] According to tradition, it was Leonard Proctor who was near Caesor and could have heard this. All told, the regiment suffered 42 killed and 28 wounded, which was the highest number of any regiment there. Colonel Prescott’s regiment also had the highest number of Patriots of Color than any other regiment.[5]

Cesar is most likely the only Patriot of Color from Westford to be present at Battle Road and Bunker Hill.[6] According to Patriots of Color, there were 13 men named Cesar who fought on Battle Road or Bunker Hill. The return of Prescott’s Regiment dated October 3, 1775 from Cambridge lists Cesor Bason of Westford having died on June 17, 1775.[7] The surname Bason appears at this point because a Mr. Francis Tinker, of Ashby, said that Jacob Bascom of Westford was killed at Bunker Hill. However, no such person existed. Bason seems to be some combination of Bascom and Burn.

Cesar was owed £3 11 shillings for the 26 miles he traveled in Prescott’s regiment. On February 16, 1776 Abijah Wyman certified that “Cesor Bason” was a soldier in Colonel Prescott’s regiment and was slain at Bunker Hill and that he hadn’t yet received his coat and blanket as a bounty granted him by Congress.[8][9] On March 15, 1776, there was an order for a bounty coat or its equivalent in money. A bounty coat is a heavy coat offered as an enlistment bounty when men enlisted for a 8 month period, as Caesor did. It is awarded (or its equivalent in money) at the end of the enlistment period.[10] Caesor’s bounty coat was paid to Westford Selectman Zaccheus Wright on behalf of the family.

It is assumed that Caesor was buried somewhere near Breed’s Hill with other soldiers. Though he was once enslaved, he served with dignity and hope- believing in a future more just than his past. That service, and that hope, will not be forgotten.

[1] Westford Town Records, Volume II, 1764-1790, 167.

[2] William B. Prescott, Taxation of Slave Owners in Colonial Westford, Private Printing, Westford Museum Files.

[3] Letter from William Prescott to John Adams, 25 August 1775, Massachusetts Historical Society Collection. https://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=727&pid=2

[4] Reverend Edwin R. Hodgman, History of the Town of Westford, 112-113.

[5] George Quintal Jr., Patriots of Color: “A Peculiar Beauty and Merit”: African Americans and Native Americans at Battle Road & Bunker Hill, Division of Cultural Resources- Boston National Historic Park: Boston, 2004, 179.

[6] George Quintal Jr., Patriots of Color: “A Peculiar Beauty and Merit”: African Americans and Native Americans at Battle Road & Bunker Hill, Division of Cultural Resources- Boston National Historic Park: Boston, 2004, 247.

[7] Muster/payrolls, and various papers (1763-1808) of the Revolutionary War [Massachusetts and Rhode Island] Volume 16, Page 76

[8] A memorial of the American patriots who fell at the battle of Bunker Hill, June 17, 1775, Boston City Council, Boston 1896, 110. https://archive.org/details/memorialofameric00bost/page/110/mode/2up?q=bason

[9] Muster and pay rolls vol 57 page 62-63 file 7

[10] Quintal, 14.