David Iver Olsson was still a baby when his parents emigrated from Sweden to the United States and settled in West Chelmsford, Massachusetts. Hard work, devotion to family, and a kindly, caring manner sum up who this man truly was.

David Iver Olsson was still a baby when his parents emigrated from Sweden to the United States and settled in West Chelmsford, Massachusetts. Hard work, devotion to family, and a kindly, caring manner sum up who this man truly was.

In 1917, David married Beatrice M. Sutherland, whose parents lived in Westford Center. The two families quickly became lifetime neighbors and friends. The Olssons adopted two daughters. Dorothy, the older child, died at age 17 from rheumatic fever. Madeline – Maddy – and her husband, Anthony Sambito, raised their children, Bob and Martha, at 12 Boston Road.

David Iver Olsson died in February of 1979 in Westford.

My Days in the Granite Quarry

David Iver Olsson. I was born in Sweden – Sundvall [Sundsvall], Sweden. That was in 1891. I think we came to Westford in 1894. I was only about two years old when we came across. Of course, at that time we went to school. We were about five or six when we went to school in West Chelmsford.

When we had vacation from school, we used to go up and help our father to cut paving [at H.E. Fletcher Company. Today, Fletcher Granite Company, Inc.] It’s near the Chelmsford line [on Rt 40]. It is in Westford though.

That was piecework. We would go up on Saturdays to do what we could to help him by tracing and drilling holes, and doing the best we could. We were about 10 or 11 years old.

The granite was used mostly for curbing and street work, and then, of course, through the years they used it in building work, but it was a type of granite that was more adapted for street work and building work. It was that type of granite. They made some monuments, but it wasn’t adapted for that. They still do, I think. It was a softer granite – monumental granite. It’s a good granite, but it’s a different type of granite. There’s enough to last for years and years.

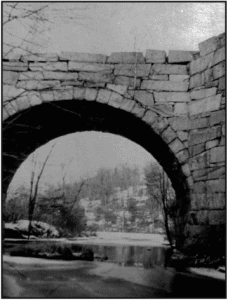

When I was there [the quarry] was around 100 feet deep. It covered an area, as I remember, of around 14 acres that had been quarried out of there. I suppose that’s a lot bigger now, a lot bigger area quarried out since then. That whole hill up there is granite, so it will take them a long time to quarry all that granite out. I don’t expect them to do that in the next few years, I know that.

When I was first married I worked in a weaving mill. Then I took a job in the quarry in the summer. We did the best we could. For two or three years, my brother and I had a little quarry we ran up on Oak Hill [where Villages at Stone Risge are now off 120 Tyngsboro Road]. Oh, we got along the best way we could.

When I first went to work [at Fletcher] I worked carrying tools, and then I served my time as a stonecutter, curb cutter, and did building work. Had to serve three years before you could join the union at that time, so I served my three years. Then I worked at different quarries. I worked at Fletcher’s quite awhile, then I went from there and I worked awhile in Concord, New Hampshire, at Swenson’s. I went from there to Milford, Massachusetts for a year or two. There we did a lot of building work. All types of work.

I think [Fletcher] owns several quarries. I think they own one or two in Maine and New Hampshire. Of course, Fletcher’s in Westford was the largest. [Fletcher Granite Company, Inc. owned quarries in Stonington, Maine; Milford, Mason, Redstone and Madison, New Hampshire and Milford and Westford/Chelmsford, Massachusetts.]

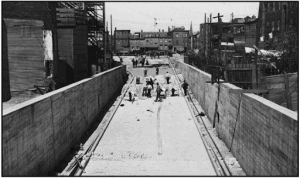

I worked a good many years in the quarry. I think I was in charge of the paving department up there at Fletcher’s for 20 years. We shipped paving practically all over the country by rail. I couldn’t tell you just now where we shipped it all. We shipped a lot of building work.

While I was in charge of the paving department, we furnished the block for the Sumner Tunnel. I think I had over 100 men working for me then. I know we shipped over a million blocks into the Sumner Tunnel at that time. My wife was the first woman to ever go through that tunnel. The tunnel hadn’t even been paved. The paving was there, but it hadn’t been paved when we walked through the tunnel. The engineer invited the wife and I to go down there to have dinner with him, and then he took us through the tunnel. The wife had the greatest kick out of that. They dumped a lot of paving in the tunnel. It hadn’t been paved, and we had to crawl all over it to get through the tunnel.

[The granite] was shipped by truck. We trucked it down, and they brought it into the tunnel and dumped it. Of course, in the tunnel, as I remember it then, the bottom floor was all cemented. The walls hadn’t been completed. [Sumner Tunnel opened in 1935.]

There is a lot of curbing in Boston from Westford. And also in Lowell and nearby cities -Lawrence and Haverhill. We used to ship a lot down to Haverhill and the nearby cities.

At the last part of it they sawed the granite. As I remember, some of them buildings, then, would be sawed granite, which would be only about 4 inches thick for a facing. But, of course, years ago most of the buildings were made of big granite blocks like the Lowell Post Office. You can see at the Lowell Post Office where real heavy blocks were put in there. [That is Fletcher granite.] That’s not true now.

All cut by hand. We called it pointing or . . . I don’t know, I can’t remember now. Chipping, and cutting curbing, you know. We’d have to cut the tops. We’d have to line them up first, and then put lines around them with a chisel, and then we’d have to point the interior out. After we had pointed it out we would have to use . . . what the dickens did we call them now? I forget now. I can’t remember.

We drilled the holes first, and then put wedges in to split a stone.

[They called the chips from the granite] chicken grit. They used it as chicken grit. I don’t know too much about that, but I know they were doing that years ago. I don’t know how much we sold. They bagged it in paper bags and sold it. I brought some home for my own chickens here at times. The bottom of this driveway here is a lot of crushed stone that we used. After I dug it out, I had several loads of granite brought up here and dumped and leveled up as a base for the driveway. Not only me, everyone used to do that quite a bit. In fact, I had some trucked up to my father-in-law’s home. I had his driveway all dug out and leveled off and covered with hot top. It would be a rough road if you just had the chips. Lots of times, after we put the stone chips in, we’d put some gravel on and smooth that out, and then have the hot top put on.

I remember the Fletcher’s railroad went from Fletcher’s quarry to the main road in Brookside. I remember when that road was built. I think I rode on it when they first opened it up. I remember before that they used to have horses and oxen, I suppose, in some of the back quarries but I don’t know too much about that.

At times it can be quite dangerous. Of course, stone is heavy. It has to be handled with caution and, at times, you can hurt yourself, hurt yourself seriously if you’re careless at all. It is a dangerous type of work. It was then, anyway. I don’t know what it is now. I suppose it is now. [When I] was as a young boy, this fellow was running what we called a steam drill. I think that was an old-fashioned steam drill. It runs by steam. And he was up on this tripod, and they hollered for him to get out of the way, to be out from under the derrick. He stood there looking up like that, looking up at the stone when it was going by, and just as that stone went over him, the chain broke. It came down, and, of course, it killed him. I can remember what an awful impression it made on his brother working nearby. He’d seen it all. I know it made an awful impression on me. I was standing at the edge of the quarry looking down when it happened. I was up there helping my father.

[When] I was working in Milford, Massachusetts, I was hitting this side of the handset. I was chipping off some stone there and a piece of steel from that handset broke off. I got it in my eye. I spoke to the man next to me. We used to call them “buddies.” I said, “Will you pick that steel out of my eye?” He reached up with his fingers and picked the steel out of my eye. And then, I remember, after that happened, I had to walk from where I worked in the stone shed there, up the tracks for at least two or three miles, up to where I boarded. When I got up to where I boarded, there was a Mrs. Hatch, I think her name was. There was an eye specialist that lived right across the street from there, and she got him up. Then, I had to walk a couple of miles down to his office in Milford, Massachusetts, the city, and he fixed me up the best he could. How well I remember that! He done all he could for me, and then I had to walk back. She helped me the best she could, where I was boarding there. It was quite a while before they could relieve the pain. She gave me ice presses to put on my eye..

[In Westford once] I went to help. I was going to walk by a fellow, to go get up to my car, and I see the fellow was hooking onto a stone to turn it over, a big flat stone. So I thought I’d try to help him. We had, on a locomotive crane, a drill for drilling holes, so that a hook would hook in good. I hadn’t noticed that he had just taken the drill. It was one of those small drills, and he drilled a hole. I should have stopped it right there, but I was afraid mine might slip on him, so I told him to be sure to get out of the line of mine, should it let go. When he tried to turn the stone over his hook let go, and it hit me in the face and knocked me into a pile of grout. I’ll never forget that! Finally, they got me picked up out of that grout pile. I got up and over the bank from where I was, got into the car and drove up to the office, and the first-aid man up there fixed up my nose the best he could, and he said, “You’ve got to go to the hospital!” I said, “All right.” So I got into his car, and he took me down to the hospital and, of course, the doctors there fixed up my nose and put tapes on. I always remember one of the doctors said to me, “You know, noses are made to be broken.” I said, “Well, I hope the next one is yours!” I wasn’t out of work long. That afternoon I was back on the job. If I had had goggles on, in fact I wouldn’t have gotten that in my eye, probably. It was quite a job to get them to wear goggles. Of course, they were hot and you’d perspire. It was just hard to convince people they should wear goggles.

We had no [insurance]. Nothing. But what they took care of you the best they could, I suppose.

[In the winter] the stone froze, of course, and you couldn’t quarry the same as you could when the frost was out of the stone. You had to know the different types of granite and how to work them. The biggest difficulty in granite, with using a frozen stone, was what we called across the grain, hard grain. On the rift of a piece of granite, it would split pretty good. But on the hardway, across the grain, it was almost impossible. You never knew what it was going to do. Just the same as a block of wood. You know if you take a block of wood that’s been sawed, you can stand it up on its end, hit it on the end – split it with an ax. And granite is about the same principle. The rift would be the down grain. If you laid that block of wood flat on the chop block and hit it that way, you could never split it, and that’s the same with granite. At least I always felt that way.

Many a times we were frozen too. We had to get along the best we could. [My father] sometimes would pick out a boulder somewheres and cut paving in the winter when he could, and that way he could accumulate quite a few paving and he would sell them in the spring. That used to help us a lot. I remember one year – almost across from a place where we lived – there was a big boulder, and we prepared that. We’d go over there in good weather and drill and split the granite, through the hardway, when it wasn’t frozen. Oh, yes. Then after we made the hardway cuts, we could cut it on the rift [turn the stone once and then drill and split on the rift]. We could do that no matter how frozen it was. I forget what that old fellow’s name was. He said he was sure glad to get rid of that big boulder. The boulder was probably 15 or 20 feet long and probably 10 feet high. We got a lot of paving out of that. McGregor, I think his name was. We got a lot of paving out of that for that winter. It helped my father a lot, and in the spring he sold it. I think he sold it to Mr. Fletcher. He’d buy the paving so it helped a lot.

Mr. Fletcher [Herbert E. Fletcher, owner of the quarry] was a wonderful man. I want to bring that in. He was kind of tall, not too tall, but he wasn’t a heavy man at all. What could I say? He was 6 feet or something, and thin. He wasn’t a powerful man, but he was a good man. He was so fair to his workers. That was the impression I always had.

I asked Mr. Fletcher one time, “Why do you have such faith in me?” All he said – nothing could have pleased me more – he said, “David, you are your father’s son.” That was enough for him because he didn’t know me too well. No more than any other young man, but nothing could have pleased me more, because my father couldn’t even talk to him. For one thing he was hard of hearing and, of course, he couldn’t talk English.

Going to work, I found some money in the street, rolled up on the sidewalk, and in those days, “finders were keepers.” When I came home and told my mother and father about the money I’d found – it wasn’t very much, $11 or $12, or whatever it was – my father said, “David, my son, you know it is not yours.” We had to go and put a sign in the post office about the money found, and we found out who it was that had lost it. Some old lady, as I remember it. But I always remember my father – he said, “David, my son, you know it is not yours.”.

Building on Boston Road

The [steps to this house] were brought from up there [Fletcher’s quarry]. I built this house [12 Boston Road] in ’31. I can remember we moved into this house and put the fire in the boiler on Thanksgiving Day, I think. I built this house from scratch. I bought the lumber and arranged the help. This was nothing but a big orchard. I had three acres over on Route 40 and I was thinking of building there, but my father-in-law, Mr. Sutherland, wanted us to come up with him in the worst way. He lived in the big house up there [6 Boston Road], right next to the firehouse [Westford Museum and Cottage]. He owned these 2 acres here, you know. He said, “If you’ll buy some land here, I’ll sell it to you for what I paid for it.” And I said to the wife, “It’s up to you. If you’d like to, why we’ll do that.” My father-in-law wanted to sell us a 100-foot frontage, and down to the wall [in back]. So he said, “I’ll step it off,” and he stepped off the frontage. He stepped it off with his feet. It was supposed to be 100 feet and I think he stepped off 100 feet. It came within a foot or so of what it was supposed to, and that’s what’s with this house now.

That little house [at 10 Boston Road], the wife and I built that for Maddy when she first got married.

The little house up there [at 8 Boston Road] was my wife’s brother’s. He never married. After the folks died he was alone in the big house, and I said to the wife we’d build that little house for him right next to the [6 Boston Road] house, because he couldn’t live in that 10-room house up there. So that’s what we did. We built that little house. I helped hammer nails. My wife and my father-in-law, they got together what they wanted for the house. They drew whatever she wanted. I said, “You’re going to be living in the house. You’re going to run the house.” So I left it mostly [to them]. The only thing that I wanted to have [was] a ramp going into the basement because I had a lot of hens out there. Sold eggs every week. Woodland Dairy used to come up and clean me out every week. Sometimes I’d have six or eight cartons of eggs, you know, big boxes of egg cases. Woodland Dairy was Watertown, or… yes, I think they were from Watertown. They used to come up and drive up to my back cellar every week.

Down back here I had six or eight rows of raspberries, all the way to the wall. We used to pick them and sell them. Ten cents [a pint]. Two for a quarter. And lots of times we’d ship them down to Boston. Maddy would be out there helping us pick raspberries at times, too. We used to peddle them down to Lowell, peddle them most anywhere. [Maddy sold raspberries by the pint from her home at 12 Boston Road into the 1980s.] There were a lot of berries and apples and stuff grown here in years gone by.

[From June Kennedy’s book Westford Recollections of Days Gone By; Recorded Interviews, 1974-1975, A Millennium Update (2006), pp. 260-270. Edited for the Historical Society February 2019 discussion group with June’s permission.]