United States Marine Corps, Women’s Reserve, World War II

United States Marine Corps, Women’s Reserve, World War II

By her daughters, Kate Farley and Anne Farley, and Heather Monahan, Senior Administrative Assistant at Westford Cemetery & Veterans Services

Beatrice Scott (“Scotty”) Farley was the first woman from Westford ever to join the Marine Corps and among America’s first women Marines when the Corps opened their ranks to women in 1943. We hope this brief biography of Scotty’s long and amazing life will give the reader an appreciation for an inspirational, loved and deeply missed Marine, mother, wife, grandmother, sister and friend.

An Idyllic Forge Village Childhood

Beatrice Scott Farley was born in the Boston neighborhood of Dorchester on February 22, 1923 and grew up with her siblings in the Forge Village section of Westford. Her grandfather, Alexander Scott, arrived in America from Dundee, Scotland to work in the woolen mills. He met and married Jennie Baillargeon, a mill worker from Winchendon, MA. The Scotts had two children: Everett, who ran Scotty’s Service Station in Forge Village; and Scotty’s mother, Eva, who worked as a doffer in a woolen mill. Eva married Lorenzo “Joe” Lefebre, Scotty’s stepfather, when Scotty was 2 years old. Joe was a veteran of WWI and very active in the American Legion and VFW. He was later joined at the Legion by Scotty’s brother Bob, who served in the Korean War. Joe died in 1957 at the age of 58. Scotty’s mother Eva died in 1964 at the age of 59.

Scotty was the oldest of five, her younger siblings being Bob Lefebre, Pearl (Lefebre) Nyder, Ursula (Lefebre) Kittridge and Jean (Lefebre) Borges. As a young girl her grandfather gave her the nickname “Tootsie,” because she would always dance to the song “Toot, Toot, Tootsie.” She was also known as “Tootsie Scott” in the village. She much preferred the nickname “Scotty.” She had a lifelong love of Forge Village (she considered it “the capital of Westford,”) and had such idyllic memories of her childhood that her children later teased her that she sounded like Betty White’s character Rose Nyland on the TV series “The Golden Girls,” who recalled her wonderful childhood in the fictional town of St. Olaf.

Scotty’s family lived at 39 Pleasant Street at the corner of Pine Street. Her grandparents Alex and Jennie, with whom Scotty lived until adulthood, were next door at 37 Pleasant. She was very close to her grandparents and proud of her Scottish heritage. She later told her children that as a little girl she could visualize big changes in the future, like predicting that one day people would actually be able to see each other when they spoke on the phone. She grew up in a world where outhouses were the norm and the radio was a main source of family entertainment. She remembered how she would stamp her feet on the ground when visiting the outhouse to first scare away any mice or rats that might be hiding in there. She and her friends would often run outside to marvel at an airplane flying overhead. In a lifetime that would span 95 years, Scotty saw the introduction of many innovations that we now take for granted and the huge changes and improvements brought to American life.

lived until adulthood, were next door at 37 Pleasant. She was very close to her grandparents and proud of her Scottish heritage. She later told her children that as a little girl she could visualize big changes in the future, like predicting that one day people would actually be able to see each other when they spoke on the phone. She grew up in a world where outhouses were the norm and the radio was a main source of family entertainment. She remembered how she would stamp her feet on the ground when visiting the outhouse to first scare away any mice or rats that might be hiding in there. She and her friends would often run outside to marvel at an airplane flying overhead. In a lifetime that would span 95 years, Scotty saw the introduction of many innovations that we now take for granted and the huge changes and improvements brought to American life.

At age four Scotty met two-year old Mary Lord, her neighbor who would be her best friend for the rest of their long lives. Mary was born in Forge Village, the daughter of David and Mary (Kelly) Lord. She worked at the Abbot Worsted mill for many years and later ran Cote’s Service Station in Forge Village with her husband Hervey Cote, who she married in 1953. She and Scotty grew up and grew old together. The Lord and Cote families were large and well-known in town and Mary had many relatives who served in the military, including her four brothers and two sisters.

Scotty was an athletic and active girl who excelled at swimming and skating at Forge Pond behind her school, Cameron Grammar School, which is now the Cameron Senior Center. She regularly swam across the pond and as a mother could skate faster and longer than her kids. “She was the best swimmer I ever knew,” said her friend Mickey Crocker, who was best friends with Scotty’s sisters Pearl and Jean. “She could swim across Forge Pond faster than any man!” Her daughter Kate remembered one time when a boy fell on the ice and dropped his hockey stick, and her mom picked up the stick and stole the puck.

Scotty graduated from Westford Academy in the Class of 1940. She was a member of the Westford Academy Alumni Association for the rest of her life and “never missed a reunion” or alumni banquet, said Mickey Crocker, who served as president of the association for many years. (Scotty’s daughter Anne thought her mom missed only one reunion up to the 70th, when she was 92). Many of the WA classmates stayed lifelong friends and loved getting together to chat about old times. “It seemed like every boy in the classes of 1941-1942 went to war,” said Mickey. Mickey’s aunts Winifred C. (McKniff) Hulslander and Eileen (McKniff) Crowley joined several Westford women who also felt compelled to serve in WWII. After graduation Scotty was among them, not contented to sit out the war on the sidelines at home or working in a factory.

Like many people in Forge Village, Scotty worked at the Abbot Worsted mill for a short time after high school. Just as her mother Eva before her, Scotty was a doffer—this meant that she spent long hours on her feet removing the bobbins and spindles of spun wool and cotton from the textile machines and replacing them with empty bobbins to be refilled.

First Woman Marine from Westford (and Forge Village!)

First Woman Marine from Westford (and Forge Village!)

The United States entered World War II after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. The following year, an amendment to the US Naval Reserve Act of 1938 established the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve (MCWR) as a branch of the Marine Corps. The Marines were the last service branch to form a women’s reserve, 167 years after their formation (although it is true that 305 women, known as “Marinettes,” served in a clerical capacity during WWI). In February 1943, the fierce battle at Guadalcanal made it obvious that every able Marine would be needed to win the war. The USMCWR women recruits would handle the stateside roles to “free a Marine to fight” on the front lines. The official announcement of the formation of the USMC Women’s Reserve that opened enlistment to women was made on February 13, 1943.

Scotty immediately decided that this was exactly what she wanted to do to serve her country. The age requirement was 20-35, so on her 20th birthday — February 22, 1943 — Scotty took a day off work at the mill (“Is this an absolute necessity?” asked her supervisor) to join the Marine Corps with her friend Rita Thompson. Although she was an adult, as a woman Scotty was required to have a permission slip from her mother. Her friend Rita ultimately decided not to enlist, Scotty later said, because she didn’t like the style of the hat. Scotty was among the thousands of women nationwide who had swamped the procurement offices since the first day women were allowed to enlist nine days before.

Scotty found herself among the nation’s first class of women Marines and a part of American history. Although women in military uniform were considered a novelty in the world at the time, over 350,000 American women enlisted to serve in the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marines during WWII. Approximately 20,000 women joined the Marine Corps in the next three years. Scotty felt that because the Marines had just begun admitting women and so many men were serving overseas, perhaps there was more opportunity to contribute and be promoted. Distribution of rank and grade within the Corps was the same as for men. Although women would not be trained for combat, they were regarded as full-fledged Marines and treated as such. Women wore the same (slightly altered) uniforms as the men and were called “Marines” rather than by a nickname. The first director of the MCWR, Colonel Ruth Cheney Streeter, took steps to ensure that women felt invested and valued in the Corps.

Because the Marines did not finish preparing Camp Lejune, North Carolina as the main women’s training camp until late 1943, 722 women Marines were sent to boot camp at Hunter College in the Bronx, NY (where Scotty went), and more to Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley MA. Scotty was only 5’2” and often found herself marching near the back of the line, because soldiers were often aligned by height. While she was naturally polite, Scotty never let herself be intimidated. She was among the nation’s first class of women Marines who graduated from Hunter College on April 25, 1943 after four weeks of training.

until late 1943, 722 women Marines were sent to boot camp at Hunter College in the Bronx, NY (where Scotty went), and more to Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley MA. Scotty was only 5’2” and often found herself marching near the back of the line, because soldiers were often aligned by height. While she was naturally polite, Scotty never let herself be intimidated. She was among the nation’s first class of women Marines who graduated from Hunter College on April 25, 1943 after four weeks of training.

Scotty later recalled attending an Easter sunrise ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery, where she was thrilled to find herself just steps away from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. She forever remembered how the crowd went wild when the band played The Marine Corps Hymn during a Parade March. “I had such a sense of pride, I felt like a cartoon character with my chest puffed up and I thought I would pop the buttons on my uniform,” she told her daughters. Afterwards she heard one of the men telling an officer, “You should have seen them, Sargeant Ray, they looked like a bunch of stallions strutting their stuff!”

Scotty was assigned to the Marine Barracks in Norfolk, Virginia for her entire time in the Corps. Although it seems she did not indicate suffering from oppressive sexism, Scotty recalled many snide and condescending remarks. She remembered hearing one Marine say to another, “Did you ever think they’d ever let goddamn women in?” It was well known that the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb, had been reluctant to allow women and had slowly come around. “Like most other Marines, when the matter first came up I didn’t believe women could serve any useful purpose in the Marine Corps,” said Holcomb, “since then, I’ve changed my mind.” Many other Marines never changed their minds, and the sexism and harassment the women faced was significant. Women often felt deeply resented for taking on duties that sent male Marines into combat. But as she had hoped, Scotty rose in the ranks first to Quarter Master, and then Staff Sergeant. She passed up a promotion to be assigned to “overseas” duty in Hawaii because her beloved grandmother was ill and she worried she’d be too far from home. From Virginia, Scotty was able to return home on leave – an occasion in which her family and friends proudly welcomed back to Forge Village the town’s only woman Marine in her sharply pressed uniform.

Scotty was assigned to the Marine Barracks in Norfolk, Virginia for her entire time in the Corps. Although it seems she did not indicate suffering from oppressive sexism, Scotty recalled many snide and condescending remarks. She remembered hearing one Marine say to another, “Did you ever think they’d ever let goddamn women in?” It was well known that the Commandant of the Marine Corps, Lieutenant General Thomas Holcomb, had been reluctant to allow women and had slowly come around. “Like most other Marines, when the matter first came up I didn’t believe women could serve any useful purpose in the Marine Corps,” said Holcomb, “since then, I’ve changed my mind.” Many other Marines never changed their minds, and the sexism and harassment the women faced was significant. Women often felt deeply resented for taking on duties that sent male Marines into combat. But as she had hoped, Scotty rose in the ranks first to Quarter Master, and then Staff Sergeant. She passed up a promotion to be assigned to “overseas” duty in Hawaii because her beloved grandmother was ill and she worried she’d be too far from home. From Virginia, Scotty was able to return home on leave – an occasion in which her family and friends proudly welcomed back to Forge Village the town’s only woman Marine in her sharply pressed uniform.

About that time Scotty had been seeing a boyfriend, childhood friend and classmate Richard A. Connell. “Dickie” was the sixth of 10 children of Dolly and the late Joseph Connell who lived on Prescott St. A fellow graduate of Cameron Grammar School and Westford Academy, he worked at the Abbot Worsted mill as an assistant shipping clerk and joined the Navy in June 1943. Just a year after Scotty enlisted, Seaman First Class Connell was lost at sea while serving in the north Atlantic on February 25, 1944. His mother held a memorial mass for him at Saint Catherine’s Church and had his name etched onto the family headstone at Saint Catherine’s Cemetery. Dickie was 19 years old.

Scotty served until the end of the war, when Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945. As bases began closing, USMC command felt that the MCWR had been a necessary but temporary experiment and expected the women to disband and be discharged by the following year. Scotty asked for a transfer and took steps to be reinstated, intent on staying in the Corps. This turned out to be a long process.

Scotty served until the end of the war, when Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945. As bases began closing, USMC command felt that the MCWR had been a necessary but temporary experiment and expected the women to disband and be discharged by the following year. Scotty asked for a transfer and took steps to be reinstated, intent on staying in the Corps. This turned out to be a long process.

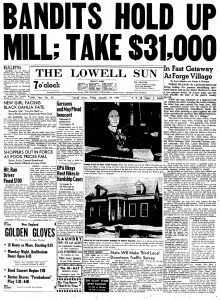

While she waited for her military plans to resolve Scotty returned to the Abbot Worsted mill, where she worked in the payroll office. On January 24 she was on the job during “the great robbery of 1947.” Five gunmen with automatic pistols burst through the front doors of the mill at 10am and made off with the bulk of the weekly payroll, totaling $31,000 (about $394,000 today). Scotty thought that the man who delivered Coca-Cola to the mill had tipped off the gang. According to Lowell Sun articles at the time, one gunman confronted the mill’s switchboard operator, Hilda Patterson, by putting his gun in her ribs and yelling, “Step aside, lady, this is a stickup!” The gang forced employees at gunpoint to the basement, where Scotty and her coworkers were processing the payroll just delivered by a Brinks truck. The gunmen ordered all the employees to lie face down on the floor. Scotty told her family that a man stuck a black shiny gun under her chin and yelled, “I said, on the floor!” She was the last person to obey because she thought it was a test staged by management, and she didn’t want to lose count of her pile of dimes. After a large manhunt throughout New England the gunmen were captured and given long prison sentences. At the end of her life, Scotty was the last surviving employee who had been present at the robbery.

While she waited for her military plans to resolve Scotty returned to the Abbot Worsted mill, where she worked in the payroll office. On January 24 she was on the job during “the great robbery of 1947.” Five gunmen with automatic pistols burst through the front doors of the mill at 10am and made off with the bulk of the weekly payroll, totaling $31,000 (about $394,000 today). Scotty thought that the man who delivered Coca-Cola to the mill had tipped off the gang. According to Lowell Sun articles at the time, one gunman confronted the mill’s switchboard operator, Hilda Patterson, by putting his gun in her ribs and yelling, “Step aside, lady, this is a stickup!” The gang forced employees at gunpoint to the basement, where Scotty and her coworkers were processing the payroll just delivered by a Brinks truck. The gunmen ordered all the employees to lie face down on the floor. Scotty told her family that a man stuck a black shiny gun under her chin and yelled, “I said, on the floor!” She was the last person to obey because she thought it was a test staged by management, and she didn’t want to lose count of her pile of dimes. After a large manhunt throughout New England the gunmen were captured and given long prison sentences. At the end of her life, Scotty was the last surviving employee who had been present at the robbery.

Marriage and Family

By the time the Marines reinstated the women’s branch and Scotty received a letter saying she could remain in the Corps, her life had changed. She gave up thinking about a military career when she met Thomas Brendon Farley at the Commodore Ballroom in his hometown of Lowell in 1947. The ballroom, then located on Thorndike Street where the Gallagher Terminal now stands, hosted all the big bands and singers of the era including Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Tommy Dorsey and Frank Sinatra. Tom was the son and grandson of well-known police officers, and his brother Leo went on to become a Mayor of Lowell (1975-1976) and a state representative.

thinking about a military career when she met Thomas Brendon Farley at the Commodore Ballroom in his hometown of Lowell in 1947. The ballroom, then located on Thorndike Street where the Gallagher Terminal now stands, hosted all the big bands and singers of the era including Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Tommy Dorsey and Frank Sinatra. Tom was the son and grandson of well-known police officers, and his brother Leo went on to become a Mayor of Lowell (1975-1976) and a state representative.

Tom was also a fellow WWII veteran, a Navy man who had served aboard the USS Bunker Hill. He was aboard when she was struck by two kamikaze bombers off Okinawa on May 11, 1945. The attack killed 393 crew members, and Tom lost many friends. Most of them were buried at sea in a ceremony that lasted over eight hours, the longest burial service in Navy history. Many surviving sailors were rescued by the USS Sullivan and brought to Pearl Harbor. Tom spent over six months in a hospital in Boston with injuries and severe burns. Like many heroes, he never spoke much about his service in the war. Tom did attend many reunions for the surviving crew and when he did choose to speak, always focused on the heroic efforts of the men who he felt saved his life, rather than on his own courage and service.

Tom was also a fellow WWII veteran, a Navy man who had served aboard the USS Bunker Hill. He was aboard when she was struck by two kamikaze bombers off Okinawa on May 11, 1945. The attack killed 393 crew members, and Tom lost many friends. Most of them were buried at sea in a ceremony that lasted over eight hours, the longest burial service in Navy history. Many surviving sailors were rescued by the USS Sullivan and brought to Pearl Harbor. Tom spent over six months in a hospital in Boston with injuries and severe burns. Like many heroes, he never spoke much about his service in the war. Tom did attend many reunions for the surviving crew and when he did choose to speak, always focused on the heroic efforts of the men who he felt saved his life, rather than on his own courage and service.

After the war ended and he had recovered, Tom joined the Lowell Police Department and was the city’s first third-generation officer. He almost immediately received a commendation for saving an elderly, wheelchair-bound woman from a burning building while off duty, sustaining fresh burns to his face while carrying her down from the second floor. Tom was named Police Officer of the year in 1977. He retired as a Detective Inspector after more than 30 years on the force. Thomas B. Farley Square, near his former home at the corner of South Whipple and Lawrence streets in Lowell, stands today in his honor.

Scotty and Tom were married at Saint Catherine’s Church in Westford on August 7, 1948. They honeymooned in New York, where she and Tom took in a Red Sox/Yankees game and saw Ted Williams hit a home run. Scotty was a lifelong Boston sports fan. She and Tom moved to South Lowell where he grew up, and they settled into their home on South Whipple Street. They were both active in the Sacred Heart Church. A year later they started having children, eventually growing their family to include a son and five daughters: Thomas, Kathleen, Maureen, Patricia, Sheila, and Anne. Her daughter Kate recalled how they played dress-up in her mother’s Marine Corps uniforms. Scotty took her children to patriotic parades, but never felt the need to march in them with her fellow veterans.

Sox/Yankees game and saw Ted Williams hit a home run. Scotty was a lifelong Boston sports fan. She and Tom moved to South Lowell where he grew up, and they settled into their home on South Whipple Street. They were both active in the Sacred Heart Church. A year later they started having children, eventually growing their family to include a son and five daughters: Thomas, Kathleen, Maureen, Patricia, Sheila, and Anne. Her daughter Kate recalled how they played dress-up in her mother’s Marine Corps uniforms. Scotty took her children to patriotic parades, but never felt the need to march in them with her fellow veterans.

She and her family continued to spend a lot of time in Westford, visiting friends and the places of her youth. “We all hung out together again, this time with our babies,” said her friend Mickey Crocker. Her daughter Anne remembered her mother organizing many road trips to Washington DC after her siblings Tom and Kate had moved there, bringing along any of her children’s friends who wanted to see the nation’s capital. Scotty always wanted to visit Arlington National Cemetery and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, where “the soldiers from the 3rd US Infantry Regiment, known as “The Old Guard.” keep a constant vigil. Her mother Scotty, said Anne, was the most patriotic person she ever knew.

Scotty had a wonderful sense of humor, and her family was the most important part of her life. As a former Marine, she was not someone who told her kids “wait until your father gets home” and was a firm but kind disciplinarian. She was fun-loving and curious, always up for trying something new and for getting her kids outside for some fun. Her daughter Anne remembered her sledding in the snow at age 64. Both Scotty and Tom were drawn to the ocean, and the Farleys spent a lot of time at the beach.

As her children got older, Scotty took a job at the IRS. She then transferred to the Finance Department at Ft. Devens, where she received many commendations from the Department of the Army. She spent 20 years there and retired in 1988.

Once A Marine, Always A Marine

Scotty and Tom retired to Salisbury Beach. She remained close to Westford and her lifelong best friend Mary Cote, and together they took many trips and excursions with the Senior Center. Her childhood home was eventually bought by Mary’s brother Phil, and it was sold a few years after he died in 2011.

Scotty’s beloved husband Tom died in 1993 at the age of 71 after 46 years of marriage. He is buried at Saint Catherine’s Cemetery. She lost her daughter, Maureen (Farley) Dubay, in 2010 at the age of 54.

To the very end, Scotty was engaged and involved with her large circle of family and friends. She drove everywhere until she was in her late 80s, when her eyesight started to fail. She walked every day, outpacing any of her companions. She and Mary met often for lunch until Mary’s death in 2014, at age 89. “The bunch of us, we were friends to the end,” said her friend Mickey Crocker.

Scotty lived in Salisbury until 2015, when she moved to Marland Place in Andover. Scotty was known to say, “See you later, alligator,” to her friends and staff there. She remained vibrant through her final days. “I don’t want to go anywhere and miss anything,” she would often say.

Scotty passed away on August 5, 2018 surrounded by her loving family after a long, wonderful life.

Scotty passed away on August 5, 2018 surrounded by her loving family after a long, wonderful life.

She was so proud to be a Marine and received full military honors when she was laid to rest at Saint Catherine’s Cemetery in Westford, next to Tom and near her parents, best friend Mary, and many old neighbors and friends from Forge Village. She rests there in peace with approximately 493 veterans to date, over 260 of whom served in World War II. They were truly “the greatest generation.” Presently there are about 20 known Marines interred there and she remains the first and only woman. When daughters Kate and Anne visit their parents’ graves, they play “The Navy Hymn” and “The Marine Corps Hymn” for their mom and dad on their phones.

Scotty was a proud member of the Women Marines Association. She was a life member of the American Legion in Westford. Her name is among those celebrated at the National Women’s Military Memorial located within Arlington National Cemetery and at the Marine Corps Museum at Quantico, Virginia as the very first woman Marine from Westford, Massachusetts.

Scotty was a proud member of the Women Marines Association. She was a life member of the American Legion in Westford. Her name is among those celebrated at the National Women’s Military Memorial located within Arlington National Cemetery and at the Marine Corps Museum at Quantico, Virginia as the very first woman Marine from Westford, Massachusetts.

Scotty is survived by her son, Thomas L. Farley of Stafford, Virginia and Salisbury Beach; her daughters, Kathleen (Kate) Farley of Methuen and Ennis, Ireland, Patricia Shupp and her husband Ed of Fairfax, VA, Sheila Patton of Salisbury, and Anne Farley and her husband Phil Shea of Salisbury Beach and Lowell. She has seven grandchildren: Thomas B. Farley II, Christine Allmon, Maureen Chaisson, Roger S. Chaisson, Rebecca Hulun and her husband Rick, Richard Green, and Rachael Gray and her husband Jonathan. She was predeceased by her beloved husband of forty six years, Thomas B. Farley; her daughter, Maureen Dubay; her brother Robert Lefebre and her sisters, Pearl Nyder, Jean Borges, and Ursula Kittridge.

Not many people can say that both their parents were heroes, but the children of Tom and Scotty can. Today Tom and Scotty have to date 16 great-grandchildren and 27 nieces and nephews, who are just as proud of her as she was of them.

This brief biography of Beatrice Scott Farley began with Scotty’s obituary written by her family. Heather Monahan, Senior Administrative Assistant at Westford Cemetery & Veterans Services, also interviewed Scotty’s daughters Kate Farley and Anne Farley and their friend Mickey Crocker in April and May 2022. Heather, Kate, and Anne then wrote this together. All photos are the property of and used with the permission of Kate Farley and Anne Farley.